Medical School and Residency: Free of Charge for Students

Deli Krizova, FEBO, and Pavel Kuchynka, CSc, FCMA

Medical training in the Czech Republic lasts 6 years. At the end of training, students must complete rigorous state examinations to obtain the title of general doctor (MUDr). A recent graduate may seek employment in any clinical field of medicine.

TRAINING SPECIFICS

Ophthalmology residency is divided into two parts: basic ophthalmologic training and specialized training. Residency training takes place at workplaces that are accredited for specialized education in ophthalmology and other clinical fields.

To graduate the program, residents must complete 2.5 years of basic ophthalmological training followed by examinations and 2 years of specialized training followed by attestation examinations—a total of 4.5 years. Attestations are organized by medical faculty twice a year; the venue depends on the institution of the faculty. Fellowships are offered by individual clinics or organized centrally by the Institute for Postgraduate Medical Education.

PROS AND CONS

The country’s educational system works well as a whole. A major positive is that most of the education, including medical school and the residency program, is free of charge for students. Moreover, the residency program is revised every 2 to 3 years to reflect evolutions in medicine.

The system’s main drawback is the organization of attestation examinations. In the past, these examinations were organized by the Institute for Postgraduate Medical Education, which falls under the Ministry of Health. In 2012, the examinations were transferred to the Ministry of Education, and now their organization is handled by the medical faculties at six institutions. Periodic rotation of the examination site in a relatively small field such as ophthalmology injects differences into the conditions and organization of the examinations, which can confuse young doctors.

Transformations in Training Modules

Wanjiku Mathenge, MBChB, MMed, MSc, PhD

The goal of undergraduate and graduate medical training in Rwanda is to produce general doctors and specialists with competencies and skills that meet patients’ reasonable expectations.

The University of Rwanda is the country’s oldest medical school. It admits students who have completed 12 years of formal education, rank at the top of the cohort, and have passed the Advanced General Certificate of Secondary Education. The university’s training program requires 5 to 6 years to complete and culminates with the awarding of a bachelor’s degree in medicine and surgery with honors. The University of Rwanda also offers nine programs that confer a Master of Medicine to doctors who have performed 2 years of public service as general doctors; most of these are 4-year programs.

In order to address a massive shortage of medical doctors in Rwanda, three private universities have opened medical schools, but they have yet to graduate any doctors. The pool of doctors to recruit into ophthalmology residency training remains limited.

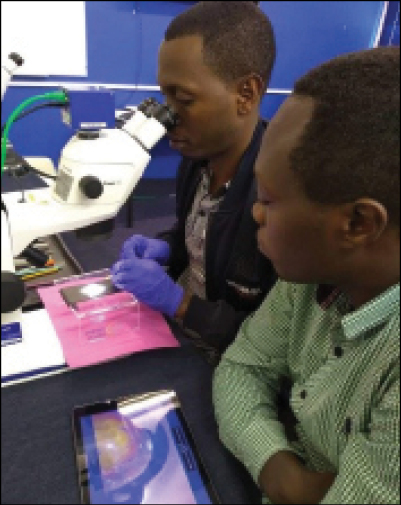

Ophthalmology residency training is the only specialty hosted not by the University of Rwanda but by the Rwanda International Institute of Ophthalmology (RIIO), a constituent training program of the College of Ophthalmology of Eastern Central and Southern Africa (COECSA). This program admits doctors from Rwanda, Burundi, and Congo, and it awards a fellowship in ophthalmology after a minimum of 4 years of training. This college-based training is becoming more popular. The emphasis is on equipping every graduate with defined core competencies, including all of the requisite knowledge, technical skills (Figure 1), and soft skills (eg, communication, ethics, patient safety, and professionalism) that are deemed to be essential in the medical profession.

Figure 1 | RIIO trainees use surgical simulation training for cataract surgery.

The program draws on the best practices of the UK’s Royal College of Ophthalmology1 and the International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO). Trainees at the RIIO must pass the ICO’s examinations in visual sciences, optics and refraction, and instruments as well as in clinical sciences before presenting for a clinical examination offered by the COECSA. Candidates must show that they have achieved all of the COECSA residency training milestones and charted their progress during clinical placements using workplace-based assessments.

COECSA has members from 12 African countries. Adoption and enforcement of the college training standards have been possible at new institutions like the RIIO, but the transition is happening more slowly at older institutions with Master of Medicine in ophthalmology training programs that are governed under institutional frameworks that existed before COECSA.2 For example, training lasts 3 years in some programs and 4 years in others. A goal of the COECSA is to develop its own written examinations and either to slowly replace the ICO examinations or to have a blend of both.

The first cohort of ophthalmology residents at the RIIO are on track to complete their training by mid-2022. Once they begin practicing in hospitals, the quality of their services will give a true indication of the value of this training model.

1. Corbett MC, Mathenge W, Zondervan M, Astbury N. Cascading training the trainers in ophthalmology across Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. Global Health. 2017;13(1):46.

2. Dean W, Gichuhi S, Buchan J, et al. Survey of ophthalmologists-in-training in Eastern, Central and Southern Africa: A regional focus on ophthalmic surgical education. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:187.

Seven Key Recommended Goals for Training

Radhika Rampat, MBBS, BSc(Hons), FRCOphth, and Andrew Scott, PhD, MD, FRCOphth, MRCSEd, FEBO

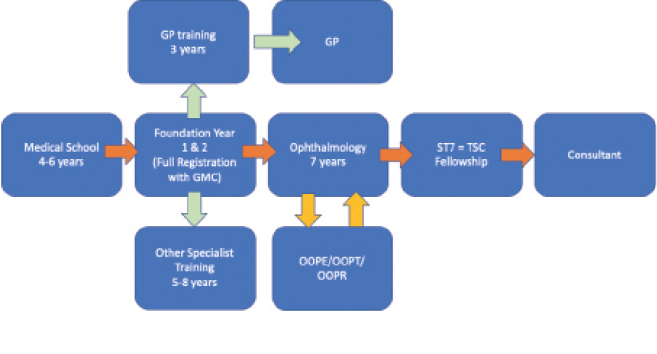

After 4 to 6 years in medical school in the United Kingdom, students graduate with a bachelor of medicine/bachelor of surgery (MBBS) degree with or without a bachelor of science degree. Full registration is achieved by completing another 2 years of foundation training (Figure 2).

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; GMC, General Medical Council; ST, specialist trainee; TSC, trainee-selected component; OOPE, out-of-program experience; OOPT, out-of-program training; OOPR, out-of-program research (eg, PhD, MD)

Figure 2 | A summary of training in the United Kingdom.

Selection into ophthalmology programs in our country is highly competitive. Participants may choose to pursue either an academic route by incorporating research into their training program or other degrees prior to application to an ophthalmology training program in order to improve their chances of selection. Each of the 7 years of training includes a rigorous Annual Review of Competence Progression, and participants must complete three tough examinations that include a refraction certificate and two Fellowship of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists examinations (FRCOphth parts 1 and 2).

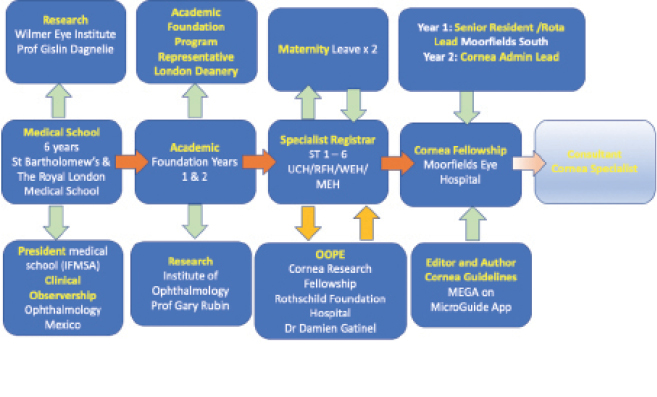

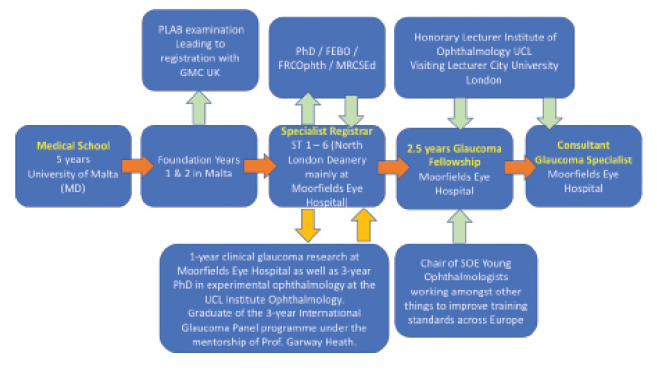

Specialty training occurs within National Health Service (NHS) hospitals, but it is the Deanery and Royal College of Ophthalmologists that ensures standards and quality of training are upheld. Clinical governance plays a major role in UK training; participants are not only taught about it but must also submit evidence of practicing it. Figures 3 and 4 show our specific training journeys.

Abbreviations: ST, specialist trainee; UCH, University College Hospital; RFH, Royal Free Hospital; WEH, Western Eye Hospital; MEH, Moorfields Eye Hospital; IFMSA, International Federation of Medical Students Associations; MEGA, Moorfields Emergency Guidelines App

Figure 3 | Dr. Rampat’s journey from medical school to present, as she embarks on consultant applications and completes her second fellowship.

Abbreviations: PLAB, Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board; General Medical Council, GMC; FEBO, Fellow of the European Board of Ophthalmology; FRCOphth, Fellow of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists; MRCSEd, Member of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh; UCL, University College London; ST, specialist trainee; SOE, European Society of Ophthalmology

Figure 4 | Dr. Scott’s journey from medical school to his current glaucoma specialization at Moorfields Eye Hospital.

QUALITY

The United Kingdom’s structured training programs are held in high regard internationally and attract participants from overseas. Because salaries for training doctors are partly funded by the Deanery, there is an incentive for NHS hospitals to provide a high standard of training in order to retain their trainees. These individuals provide invaluable work to support the NHS, and the Deanery may remove them from a hospital if the training standards are not met.

Only through high-quality training can the highest standard of care for patients be ensured (see Seven Key Recommended Goals for Training).

Seven Key Recommended Goals for Training

- Established structure

- Standardized curriculum

- Adequate supervision

- Regular appraisals and assessments

- Surgical logbook evidence

- Portfolio of training evidence and appraisals

- Formal fellowships

TIME

A complaint sometimes voiced about the UK’s training program is that it is too long, but it is the only one in Europe that incorporates a mandatory year of fellowship in a specific specialty of choice.

Moreover, the length of the program helps to ensure a depth and breadth of experience. For instance, participants are not only taught technical skills but also how to approach practice with emotional, analytical, and creative intelligence that supports their surgical independence and decision-making ability when they receive a Certificate of Completion of Training and start applying for jobs as a consultant.

possible improvements

A possible change to the system would be to reduce general training time and increase fellowship time. Efforts could also be made to develop fewer but higher-qualified, dedicated trainers. Additionally, the number of trained medical ophthalmologists could be expanded to help manage a growing burden of vision loss that does not require surgical intervention.

Integrating Competency-Based Care Into Residency Programs

Jorge E. Valdez-García, MD, PhD

The goal of graduate medical education is to ensure that physicians-in-training become competent to practice in their field of medicine. Training in ophthalmology residency programs is highly competitive.

In Mexico, medical residency is defined as a set of academic, care, and research activities that are endorsed by universities and the operative programs implemented by the clinical training sites. Each residency program must be registered with the National Medical Residence System of the Interinstitutional Commission for the Training of Human Resources in Health.

TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES

There are 13 academic residency programs in ophthalmology endorsed by universities that operate in 28 clinical training sites (hospitals), and the National Autonomous University of Mexico endorses 46% (n = 13) of these training sites.

Access. Training programs are concentrated in a few cities; the cities with the highest concentration are Mexico City (46%), Monterrey (14%), and Guadalajara (11%). Geographically, of the 32 states that make up the Mexican Republic, only 30% (n = 10) have a residency program in ophthalmology.

In order to obtain a spot in a residency program, the graduate physician must pass the highly selective National Examination of Medical Residency Applicants. Candidates compete for 292 spots (271 for Mexicans and 21 for foreigners) in the different academic programs. The largest number of training opportunities (115 or 42%) are located in the clinical facilities of the Mexican Institute of Social Security. Another 54 slots (19%) are available from the Ministry of Health. Approximately 20% of training opportunities are available through five nongovernmental organizations; one of them, Tecnológico de Monterrey, has an innovative public-private (nonprofit) approach.

Certification. After completing a 3- to 4-year training period (only three programs require 4 years to complete), residents graduate with a university degree of specialist in ophthalmology. To practice ophthalmology, graduates must obtain a cedula professional license, which requires passing the Mexican Board of Ophthalmology certification examination. This is a practical and theoretical examination.

Accreditation. Excellence in clinical care demands quality medical education. This principle has prompted initiatives for evaluation and accreditation in Mexico’s residency programs. The National Council of Science and Technology established an accreditation system for medical residencies, the List of the National Graduate Quality Program. Only 10 (35%) clinical training sites are accredited—one with an international competence level (Tecnológico de Monterrey), three with a consolidated level, and six with a development level.

CONCLUSION

Competency-based medical education is gaining strength as a solution to the challenges of the modern era. The goal is to develop Mexico’s ophthalmology residency programs to provide this type of education.

Ophthalmology Fellowships: Benefits to Looking Abroad

Riccardo Vinciguerra, MD

Ophthalmology residency in Italy is not only medical but surgical as well. In some ways, this design provides those of us who completed residencies in Italy with an advantage over those who completed residencies in countries that do not include surgical rotations. The problem in Italy is that not every resident gets the same type of surgical experience and that some do not get any surgical experience at all. It is highly dependent on the program and the faculty.

After completing a 4-year ophthalmology residency in Italy, the next logical step, I believe, is fellowship. Fellowships are not mandatory, but in my mind, they should be—especially for individuals who want to specialize in areas like cornea, glaucoma, and vitreoretinal surgery. How else are you to truly prepare for all of the procedures required in anterior and posterior segment surgery? How else can you experience fully what you’re going to do for the rest of your life?

LOOKING ABROAD

In Italy and many other European countries, there are no real fellowship programs, so those who are interested in pursuing one look abroad. One popular fellowship destination is the United Kingdom. I completed two fellowships, one glaucoma and one cornea, in Liverpool. Both fellowships took place at referral centers, which provided me with the opportunity to perform complex surgeries. It also helped me to decide which to pursue as a specialty.

Another benefit to looking abroad for fellowship is that it exposes you to other cultures, other languages, other people, and other landscapes. It helps you to grow, not only as a doctor but also as a human, through the experiences you share with colleagues and with other residents of the country in which you are living (Figure 5).

Figure 5 | Dr. Vinciguerra (left) with his former fellows Esmaeil Arbabi, MD, and Argyrios Tzamalis, MD.

NEED FOR EXPANSION

In many cases, including mine, fellowships are found through referrals or word-of-mouth recommendations. Fellowships are not in mainstream practice in most of Europe, and many of those available are in large hospitals. This is different from in the United States, for instance, where many private practices offer specialized fellowships.

Hospital-based fellowships have advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, they expose participants to a variety of surgeries. On the other, it can take much longer to learn certain things, and there is a limited amount of available technology.

If you look at the credentials of many of the rising stars in ophthalmology in Europe, you will notice that most of them have done a fellowship abroad—usually in the United States or the United Kingdom. I think there is a large unmet need in Europe for more fellowships, and it is something that as a Union we should think about improving.