Presentation. A 28-year-old pediatric intensive care unit nurse presented to the clinic with a 1-week history of redness, pain, and tearing in the right eye. Prior to presentation, she visited an urgent care center, where she was diagnosed with a right eye abrasion and discharged without medication. She wore soft contact lenses in both eyes but denied extended or overnight lens wear. Other pertinent history included exposure to multiple neonates with herpes simplex virus (HSV) at her workplace.

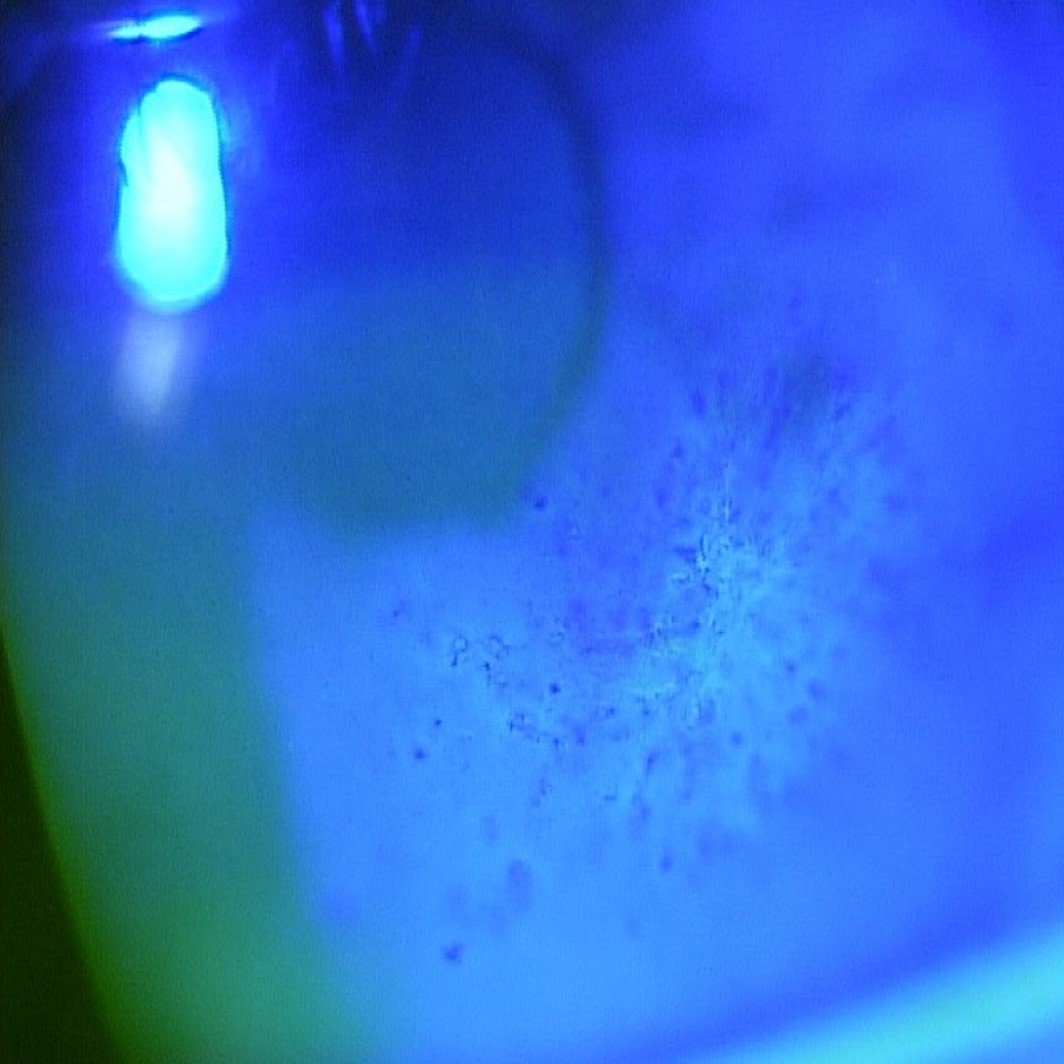

Examination. The patient’s vision was 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS, with normal IOP, normal motility, and full confrontational visual fields bilaterally. Anterior segment exam revealed several abnormalities in the right eye, including follicles without pseudomembranes in the eyelid and limbal flushing. Corneal exam revealed anterior stromal haze with epithelial staining in an atypical dendritic pattern without evidence of perineural infiltration (Figure 1). Anterior segment exam of the left eye showed no abnormalities. Fundus exam was unremarkable in both eyes.

Figure 1 | Fluorescein stain revealed atypical dendritic pattern without perineural infiltrate.

Diagnosis and treatment. The patient was initially diagnosed with herpetic keratitis and treated with oral acyclovir, topical ganciclovir, and topical erythromycin. Despite initial symptom improvement with therapy, the patient lacked clinical stability, and 2 weeks later clinical findings worsened. Potential causes of atypical keratitis such as Acanthamoeba were discussed with her at this time; antimicrobial coverage was expanded to trifluridine, valacyclovir, and ofloxacin. One month after diagnosis, topical prednisone was added due to persistent symptoms after HSV-1 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and HSV-2 PCR returned negative.

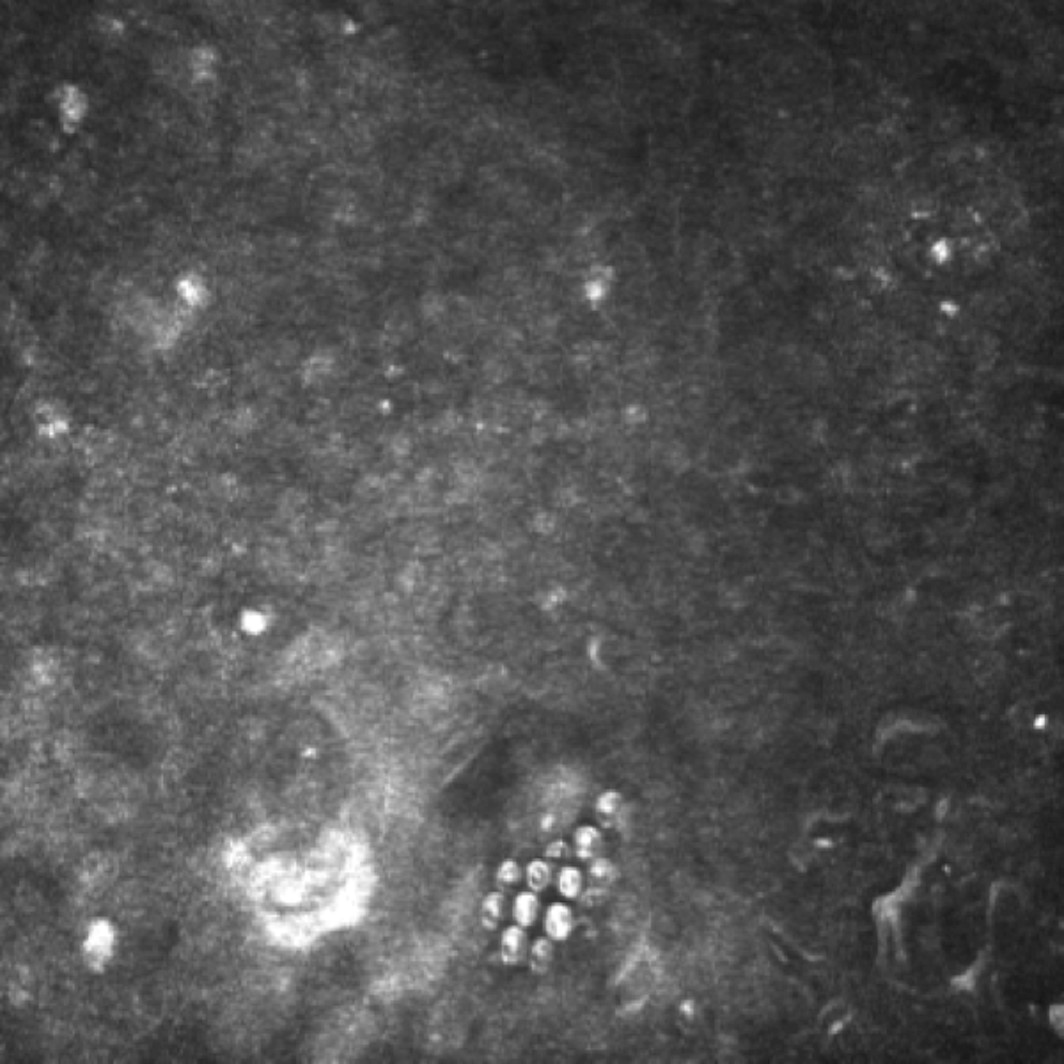

Two months from initial diagnosis, there was no significant symptom improvement. Additional diagnostic measures including cytomegalovirus PCR, varicella zoster virus PCR, gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and fungal culture with smear returned negative. A diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) was confirmed with confocal microscopy, which exhibited multiple ovoid, double-walled cysts (Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Appearance of ovoid, double-walled Acanthamoeba cysts on confocal microscopy.

The patient was started on topical polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% alternating every 2 hours, but she showed minimal symptom improvement over a month. Escalation to drops every hour produced improvement, with confocal microscopy showing the absence of Acanthamoeba cysts. Attempts to taper the regimen resulted in keratitis exacerbation; thus, the patient was returned to drops every hour. Despite a quiet appearance of the eye with every 1 hour of drops, whenever a taper regimen was implemented, she began to reflare.

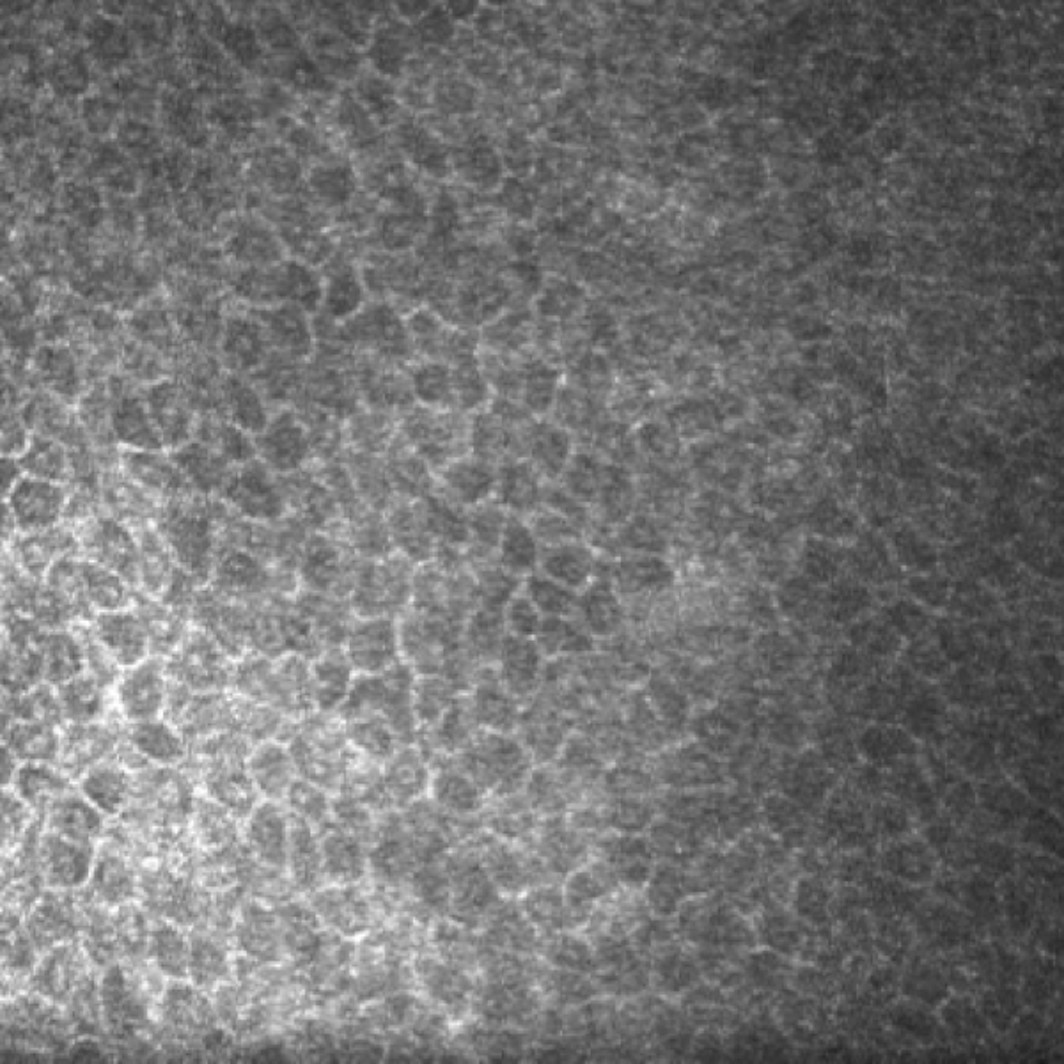

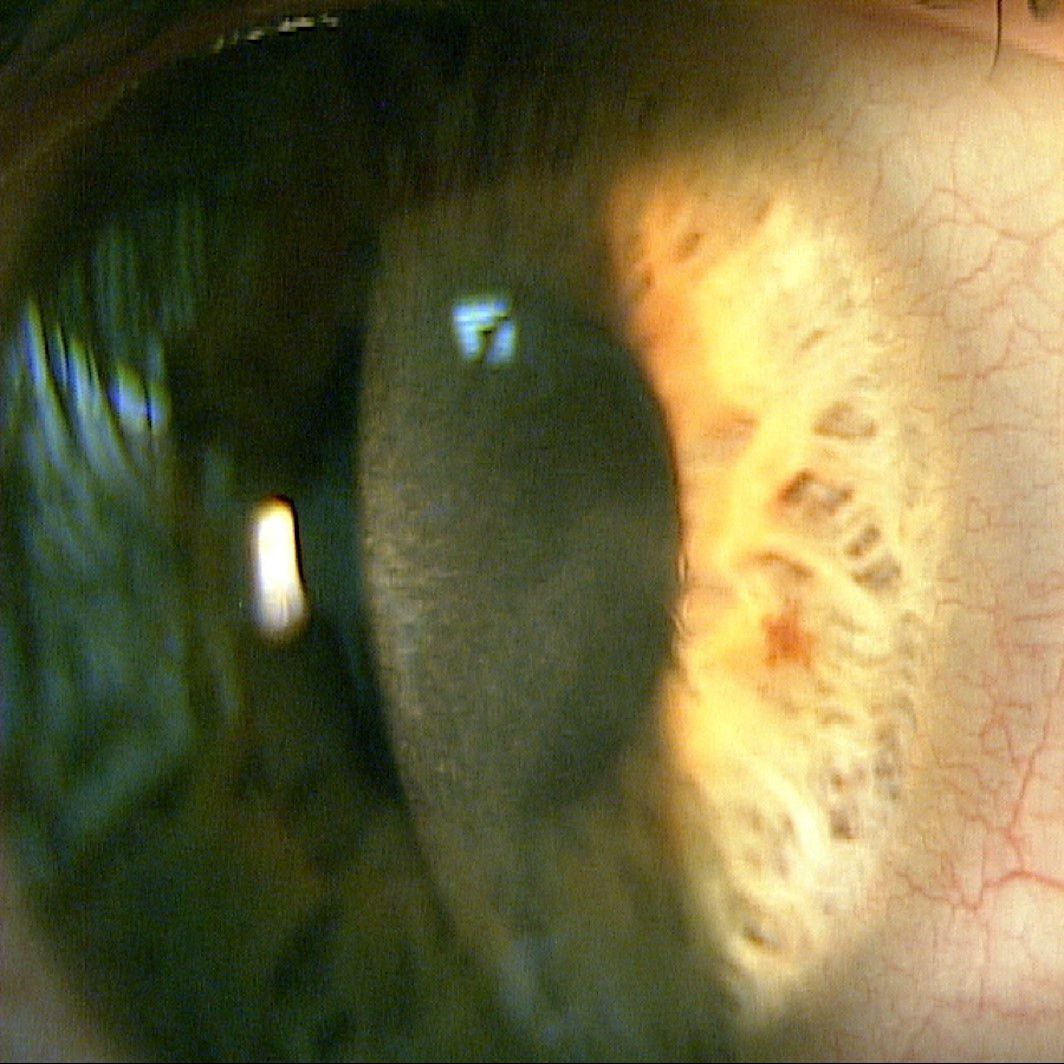

Given the context of AK refractory to medical treatment, corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) was discussed and implemented 5 months after diagnosis of AK. One month after CXL, confocal microscopy revealed no cysts (Figure 3), and the patient was asymptomatic. PHMB and chlorhexidine therapy was halted. Two months after CXL, she remained asymptomatic and not on medical therapy. Her exam showed small area of focal scarring (Figure 4), and her BCVA was 20/20 with a myopic shift and an increase in astigmatism, as expected with CXL.

Figure 3 | Confocal microscopy taken 1 month after CXL revealed no cysts.

Figure 4 | Slit-lamp exam after crosslinking revealed a small area of focal scarring.

Summary. Despite medical therapy, AK can persist and require further intervention.1-2 A promising new treatment modality involves the use of CXL, a procedure traditionally reserved for keratoconus. Riboflavin and ultraviolet light is used to crosslink and strengthen the collagen matrix in the cornea.4 CXL is thought to have benefits in the treatment of infectious keratitis, such as direct oxidative damage to pathogens and decreased penetration of pathogens through the strengthened corneal collagen matrix.3-4

Although the role of CXL in the treatment of infectious keratitis is still being investigated, this case highlights the successful use of the procedure to treat a patient with AK refractory to intensive medical therapy. Our findings are in line with other case reports treating refractory AK with CXL.3

1. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):487-499.

2. Maycock, NJ, Jayaswal R. Update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Cornea. 2016;35(5):713-720.

3. Khan YA, Kashiwabuchi RT, Martins SA, et al. Riboflavin and ultraviolet light a therapy as an adjuvant treatment for medically refractive Acanthamoeba keratitis: report of 3 cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(2):324-331.

4. Makdoumi K, Mortensen J, Crafoord S. Infectious keratitis treated with corneal crosslinking. Cornea. 2010;29(12):1353-1358.