Dry eye disease (DED) is an umbrella diagnosis, covering a set of shared diagnostic criteria for a host of presentations and root causes. To the physician treating this multifaceted disease, the complexity can seem overwhelming. How do we treat a problem with multiple causes?

To start, we can recognize that we do not have to make this hard. When we see patients with any number of risk factors, from age to medications to computer use, we have tools at our fingertips to help quickly identify the problem (or problems). Insightful, objective point-of-care testing reveals a lot about a patient’s ocular surface. Meibography (LipiView; TearScience) delivers structural information about the meibomian glands, while matrix metalloproteinase 9 testing (InflammaDry; RPS) measures the inflammatory component of DED.

Tear osmolarity testing (TearLab Osmolarity System; TearLab) helps characterize the quality of the tears, contributing to our understanding of the cause and stage of the disease. A recent convert to this technology, I now use it for all my patients and want to share how the results guide me in initiating the treatment process for DED, even if the result is normal.

PATHOLOGY OF NORMAL OSMOLARITY

When patients have symptoms of DED, an abnormal tear osmolarity score can help us confirm the diagnosis. However, a normal score does not rule out DED. At first glance, this made me question whether tear osmolarity testing was accurate or useful. As I spent time using the technology, I came to appreciate tear osmolarity testing for the insight it gives into the disease state and root etiology of DED.

A recent study showed that patients with normal tear osmolarity scores and Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) scores pointing to DED had other causes for their dry eye symptoms; these included anterior blepharitis, allergic conjunctivitis, keratoneuralgia, and epithelial membrane basement dystrophy (EBMD).1 When one of my cataract patients, a woman who looked like she had classic postmenopausal dry eye, had normal osmolarity scores, I diagnosed EBMD. I performed superficial keratectomy to smooth the ridge that was breaking up her tear film. With a smooth surface, her dry eye symptoms improved, and I was able to get accurate topography and perform cataract surgery.

In other cases, patients with normal osmolarity do have DED. Looking at osmolarity alongside the exam and other testing helps us to better characterize the disease, which, in turn, allows us to better customize the treatment process to speed relief and, if necessary, prepare the ocular surface for surgery.

One reason for this was explained by the Dry Eye WorkShop study: Compensatory tearing can occur early in the disease process, when there is also less inflammation involved.2 With this in mind, I use tear osmolarity scores to help determine treatment for meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). If a patient has signs, symptoms, and positive examination for MGD and tear osmolarity is abnormal, I typically treat the patient with traditional therapy and long-term drops, such as cyclosporine (Restasis; Allergan) or lifitegrast (Xiidra; Shire). If the same patient has normal tear osmolarity, then I know the disease is in an earlier, milder stage, and I am more likely to focus on the glands in first-line therapy, targeting the lid margin with an intervention such as thermal therapy.

A ‘NORMAL’ CASE

In a typical case of DED with normal osmolarity, a 69-year-old white woman was experiencing almost constant mild discomfort and foreign body sensation, which felt worse in the morning. Her SPEED score was 15. She had a medical history of hypertension and was taking pravastatin, metoprolol, vitamin C, vitamin D2, and calcium.

The patient had a BCVA of 20/20. Her tear osmolarity was normal (291, 292), and MMP-9 testing was negative in both eyes. Her conjunctiva showed 1+ conjunctivochalasis, and corneal staining was minimal.

Examination of the eyelids and meibomian glands showed 1+ telangiectasia in both eyes and 1+ scurfing. Meibomian gland secretions were graded 2 to 3+ in both eyes. More than half of the patient’s meibomian glands had dropped out, displaying atrophy, truncation, and acini congestion.

The patient’s age, gender, and use of metoprolol were risk factors for MGD. Her examination clearly showed mild to moderate MGD. When I added in the fact that her tear osmolarity score was normal, I could say with confidence that she still had hypercompensatory tearing with low inflammatory involvement.

The patient’s treatments for MGD included lid hygiene and lid blinking exercises, oral omegas, 50 mg minocycline, and hypochlorous acid 0.01% lid spray three times per week. I performed LipiFlow (TearScience) thermal pulsation once, and MiBo Thermoflo (MiBo Medical) was done in follow-up in two different sessions, 8 weeks apart. Warm compresses were discontinued after thermal therapies. The patient was prescribed loteprednol 0.2% four times a day for 2 weeks to treat one flare-up. After 12 months of MGD and DED management, the patient said she felt “80% better” overall.

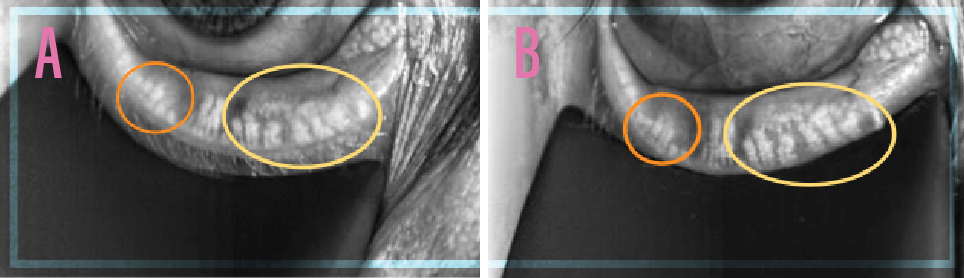

Before and after images of the patient’s meibography (Figure 1) beg the question, is reversal of early damage possible? The post-treatment meibography demonstrates lengthening of the distal glands, albeit still disorganized from disease but with more glandular material filling the prior gaps. The glands in comparison also appear less congested, with better architectural integrity of the individual acini.

Figure 1 | The patient’s meibography before treatment (March 2016 [A]) and after treatment (September 2016 [B]).

The patient’s testing and exam clearly showed that she had MGD; her normal tear osmolarity score helped me understand just how early it was in the disease progression. We were able to use thermal therapies to improve the function of the meibomian glands and restore a healthy tear film.

CONCLUSION

Outcomes like those achieved in the case described above were not possible in the past, when point-of-care testing and treatments for DED were limited. It is exciting that today we have technologies to unravel this once-perplexing disease and treat it effectively for a better quality of life and more successful surgical outcomes.

1. Starr C. The utility of normal tear osmolarity results. Ophthalmology Times. March 15, 2017. Available at: http://ophthalmologytimes.modernmedicine.com/ophthalmologytimes/news/utility-normal-tear-osmolarity-results.

2. Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75-92.