In 2014, the most common combination of perioperative cataract surgery eye drops—at least among my peers—included a steroid, an NSAID, and a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic. However, over the past few years, ophthalmology drugs, not unlike other specialty drugs, underwent unprecedented price inflation. Simultaneously, higher prescription plan deductibles, Medicare “donut holes,” and rising copays began to unmask these prices to our patients.

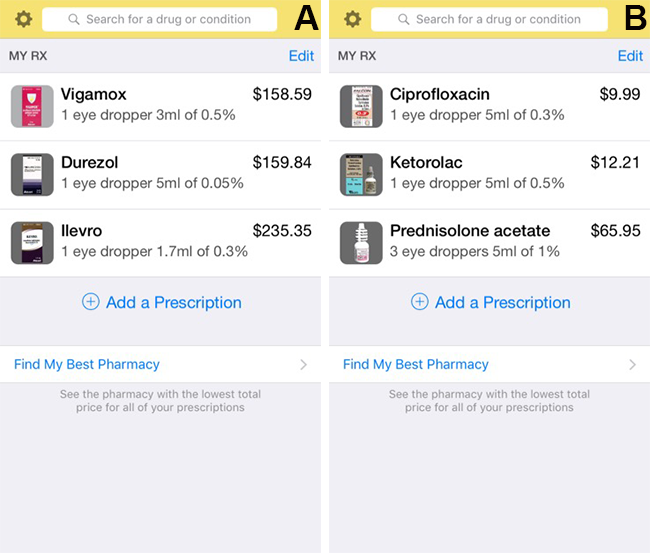

For example, as of June 2016, the cash price for Vigamox (Alcon), Durezol (Alcon), and Ilevro (Alcon) for one eye is $553.78 on GoodRx, an app that finds the absolute lowest pharmacy drug prices and offers discount coupons (Figure 1A). These prices are the best prices from an online pharmacy called PillPack and are likely higher at an independent pharmacy. A similar search for generic ciprofloxacin, prednisolone acetate, and ketorolac tallies up to $88.15, mostly due to the recently increased price of decades-old prednisolone acetate ($69.95; Figure 1B). Now, some insurance plans or Medicare may cover a portion of these prices, but all too frequently, and unpredictably, and despite proliferating manufacturer discount cards, our patients are asked to pay these full prices.

Figure 1 | Drug prices (as of June 2016) on the GoodRx app for a common combination of branded (A) or generic (B) postop drops.

Taking premium cataract surgery out of the discussion and putting the eye drop costs in perspective, the average Medicare physician reimbursement for cataract surgery code 66984, including 90 days of postop visits, is around $700 or less.1 Surgeons, looking out for their patients’ health but also minding their finances, have noted the skewed, illogical pricing dynamics and have begun to evaluate alternatives.

Twenty years ago as an ophthalmology resident, I, following my attendings’ practices, utilized one bottle of Tobradex (Alcon) on a tapering schedule postoperatively without any issues. With the advent of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in the early aughts and higher-potency NSAIDs, the current triple combination was increasingly promoted and adapted—also, it was cheap. Just a few years back, many of us remember freely providing our patients a postop cataract kit including a steroid, a branded NSAID, and a prescription for a fluoroquinolone, which never generated any patient complaints over cost or copay. The pharmaceutical company-supplied kits were done away with in the 2009 PHrMA guidelines, and look what’s happened to the costs since.

DO WE REALLY NEED THREE AGENTS POSTOPERATIVELY?

Practice patterns evolve, and we now have more evidence-based studies to guide us on our postop regimen. Intracameral antibiotics have been clearly shown to be effective in reducing endophthalmitis, and a few studies have questioned the need for postop topical antibiotics in patients receiving intracameral antibiotics.2 In addition, recent studies such as the 2015 report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology3 have questioned the need for routine NSAIDs postoperatively. Finally, surgeons such Keith Walter, MD, have been cutting out the steroid completely for years, utilizing only an NSAID as an anti-inflammatory postoperatively.

WHAT I USE

As much as I would love to have a single postop solution for all of my cataract patients, I still use a combination of prescribed generics and branded drugs, but we have started to alter the status quo.

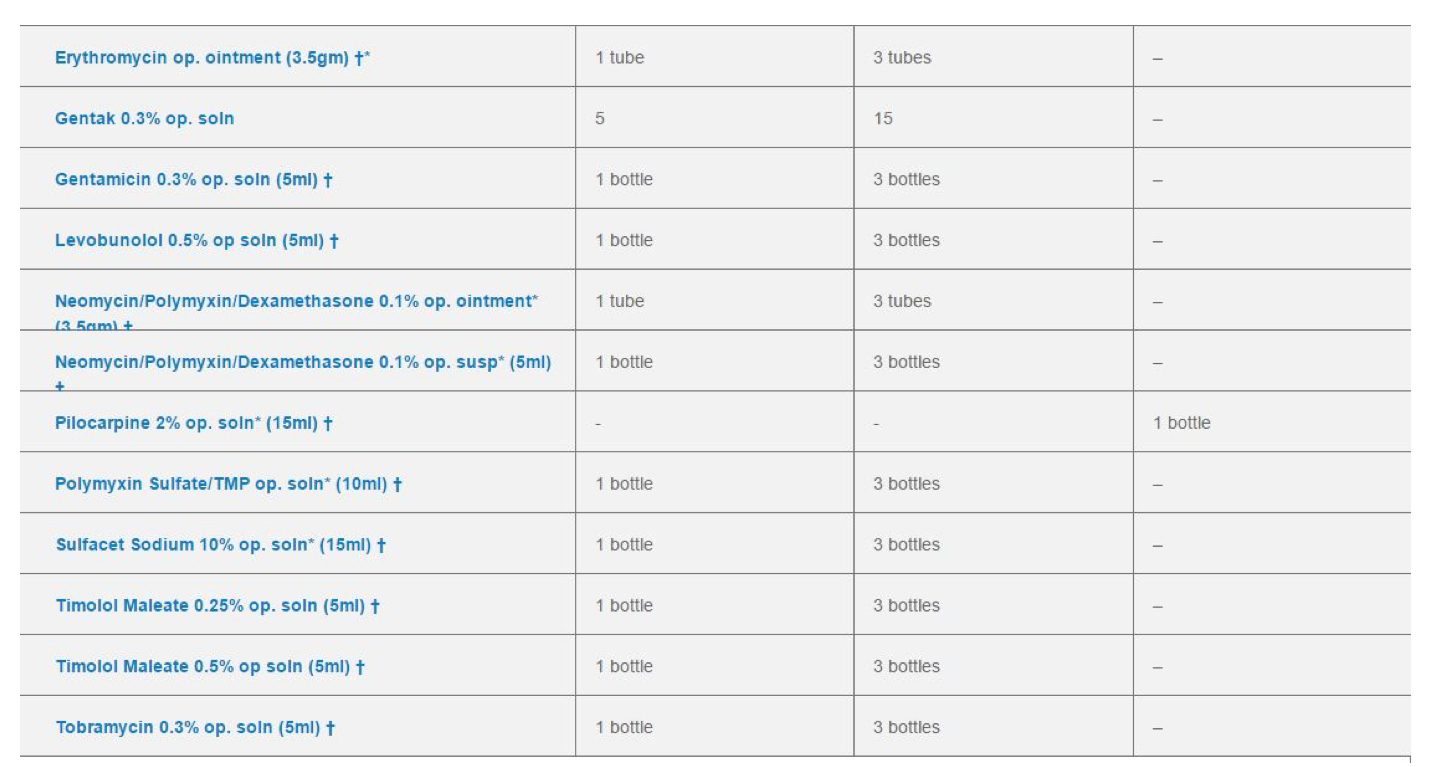

I have been placing intracameral moxifloxacin at the conclusion of every intraocular surgery for years. With the mounting literature, I have felt more comfortable prescribing generic tobramycin/dexamethasone or neomycin/polymyxin/dexamethasone 0.1% (generic Maxitrol, available for $4 at Walmart; Figure 2) for patients for whom finances are a concern. I would love to stop the antibiotic completely.

Figure 2 | A list of $4-per-month generics available at Walmart.

We now offer our patients compounded drops from Imprimis. Currently, we are using Pred-Moxi-Ketor, a one-bottle combination that we offer patients at the time of booking. This product costs between $30 and $60 depending on the quantity, and patients love the convenience of skipping the pharmacy and needing only one bottle. Pred-Moxi-Nepafenac has also become available, and we plan to try this combination soon.

Other surgeons are injecting compounded prednisolone and moxifloxacin into the vitreous cavity for a “dropless” approach, although there are some cons to this with regard to floaters and the very rare vitreous hemorrhage or worse. I have held off on this approach, but I am looking forward to other drug delivery options in development that will help our patients deal with the complexity and cost of these drops. One such product, Dextenza (Ocular Therapeutix), is an intracanalicular depot of steroids, which, if approved and used with intracameral antibiotics, may obviate the need for postop drops or at most a daily NSAID.

SUMMARY

Eye drop costs have skyrocketed, but new products and business models are emerging that ultimately should swing the pendulum back in favor of value for our patients.

1. License for Use of Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition. CMS. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/license-agreement.aspx. Accessed June 6, 2016.

2. Kim SJ, Schoenberger SD, Thorne JE, Ehlers JP, Yeh S, Bakri SJ. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cataract surgery: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):2159-2168.

3. Herrinton LJ, Shorstein NH, Paschal JF, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2):287-294.

I Don’t Routinely Use Steroid Drops in Cataract Surgery

In October 2010, I stopped using steroid eye drops in routine cataract surgery based on the evidence that bromfenac alone worked very well in the FDA trial, with only a 2% to 3% need for a rescue drop (steroid). I figured that, with my patients, I could always add a steroid if I needed, as I was seeing my postops at 1 day and 1 to 2 weeks. If there was any excessive inflammation or pain, I could add a steroid drop, but I was trying to lessen my patients’ drop burden and all of the pharmacy callbacks.

After about 200 cases, I realized that I wasn’t adding the steroid for ANY of my patients. Zip ahead to 2016, and I have now done more than 4,500 consecutive cases without a steroid and haven’t found a need for it yet, except in cases of retained lens fragment or patients with a history of uveitis. That’s it! That means I don’t use a steroid in cases in which I use a Malyugin ring (MicroSurgical Technology), in eyes with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome or dense nuclei, or in patients with diabetes. Not only did patients have no problems with pain or complaints about using less drops, they had no CME. (We did a study and found one case in 1,309 initial cases and zero cases since then.)

I know this is mind-blowing to many cataract surgeons, as we’ve been ingrained from day 1 of residency that steroids are a must—but they aren’t. You may conclude that I am this awesome surgeon with far superior skills than you (which is fine by me), or you may logically conclude that there is something to this. If you think about it, we are the only specialty that pours or injects steroids in the operative field. If you have a gall bladder or appendix removed, do you get any steroids? Nope. You have a knee or hip replaced, inject a bunch of steroids or get a Medrol dose pack? Never. So, why do we? Maybe the ocular tissues are more sensitive? Well, they probably are and most likely need some anti-inflammatory drug to help with pain, but it doesn’t have to be of the immune-suppressing, IOP-raising variety. It does have to be a good NSAID that penetrates the cells well enough to totally suppress prostaglandin formation, which bromfenac does the best of any NSAID I’ve tried.

So, if you are looking for a way to do “less drops,” I can promise you that starting with eliminating the steroid is the way to enlightenment.