Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) are a leading cause of death in the United States, representing an annual cost of more than $63 billion.1 People who have glaucoma have been found to be at increased risk of MVAs, but quantification of this risk has varied among reports.2-5 An important concern is that many people with glaucoma may be legally eligible to drive based on their visual acuity, but a state’s visual field requirements may allow individuals to drive whose ocular conditions make their doing so unsafe. We therefore set out to determine the incidence of MVAs in people with glaucoma and to identify the factors that increase their risk of MVAs.

METHODOLOGY

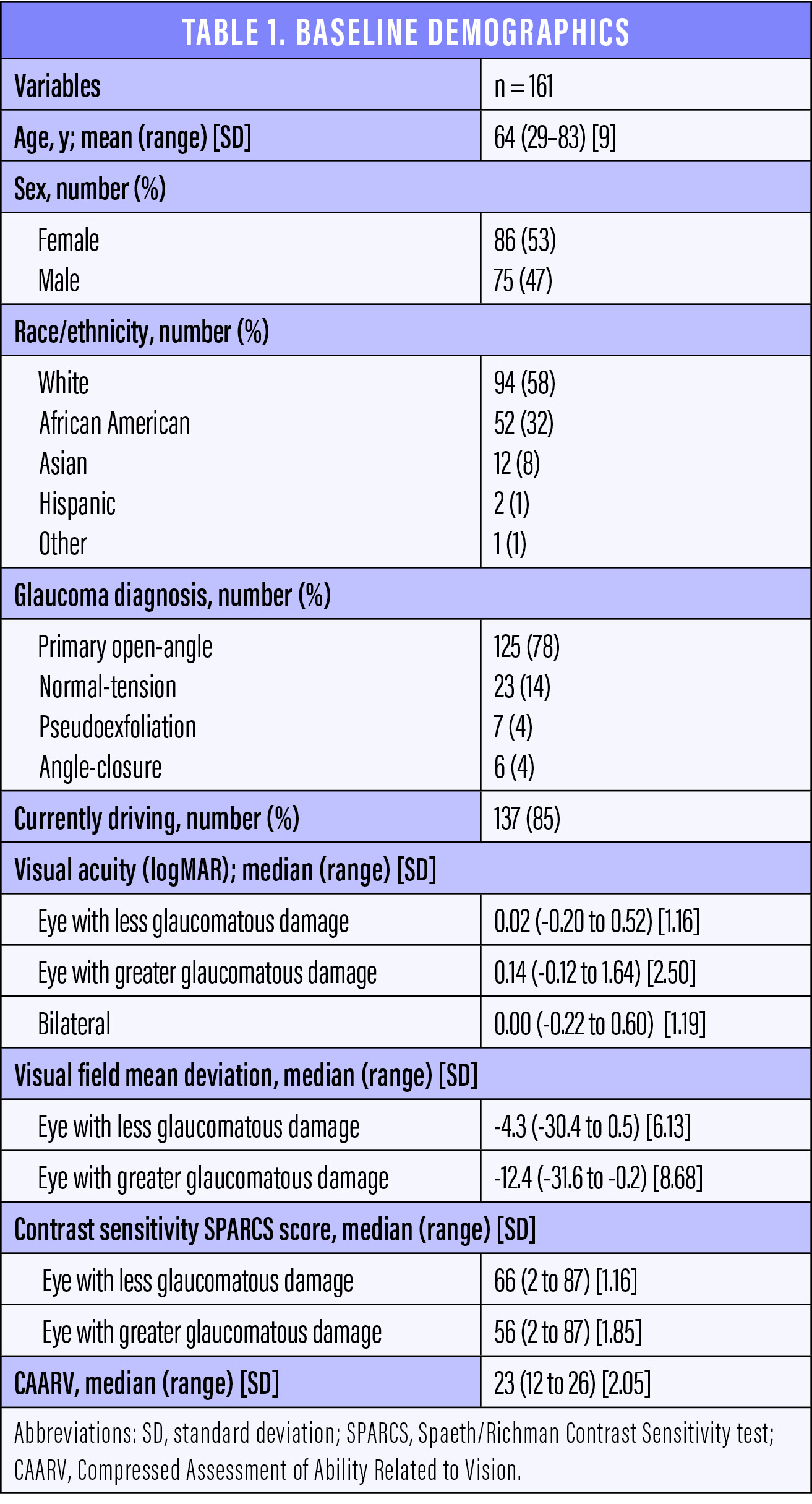

In our 4-year study, patients diagnosed with moderate glaucoma were examined prospectively at a baseline visit and again at four annual follow-up visits. Our study enrolled 161 patients whose average was 64 (range, 29–83) years (Table 1). At each visit, we assessed patients’ visual acuity, visual fields, contrast sensitivity, and ability to perform vision-related activities of daily living. We used the Spaeth/Richman Contrast Sensitivity test6 and the Compressed Assessment of Ability Related to Vision.7 We also queried patients at each visit regarding whether or not they were driving, the number of MVAs they had been in during the past year, and the parties at fault. We analyzed these data using mixed-effects logistic regression models, and we entered variables at the level of P < .10 in the univariate analysis into the multivariate model. Associations were considered significant when P < .05.

INCREASED RISK

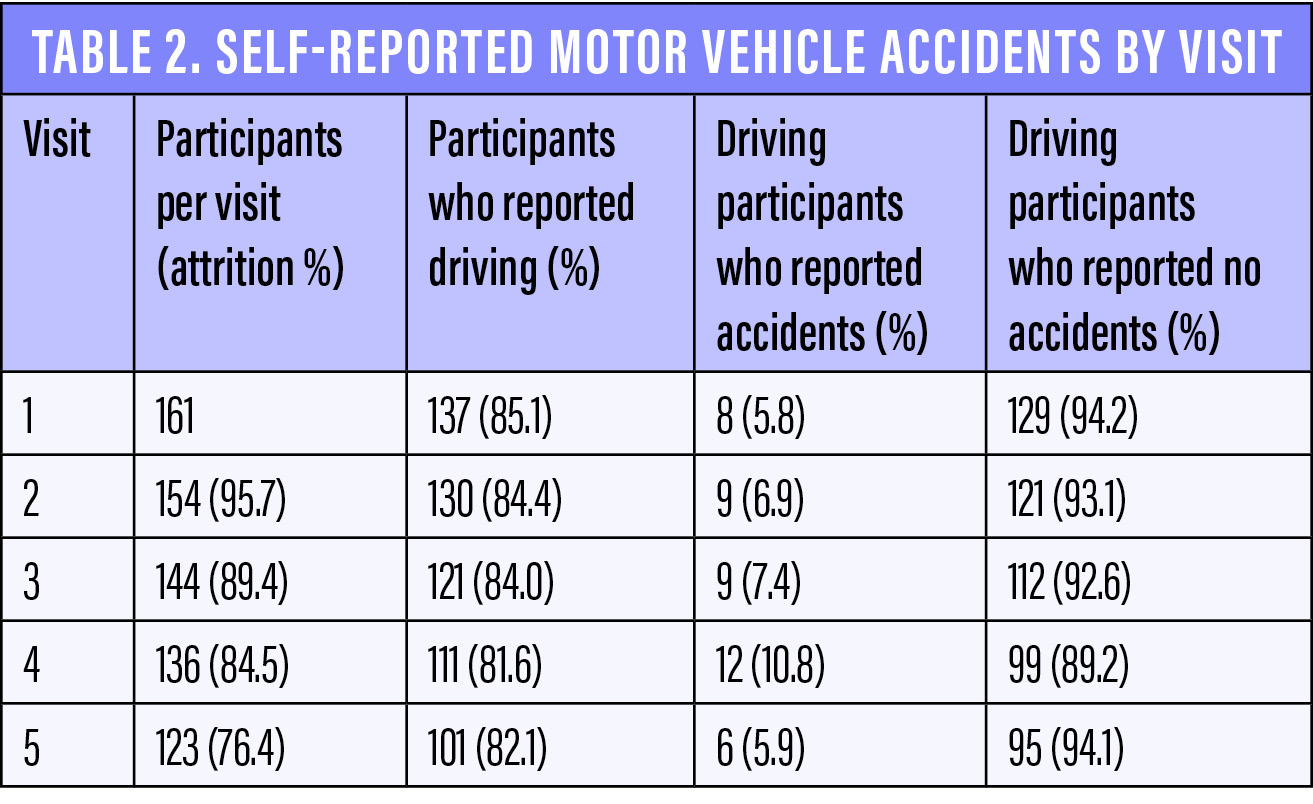

This study included 137 patients (85% of the original group) who reported driving at the first visit. The rate of MVAs increased each year, from 5.8% at visit 1 to 10.8% at visit 4, before decreasing to 5.9% at visit 5 (Table 2). The rate of MVAs among drivers at every visit was considerably higher than the rate of 1.1% in drivers aged 61 to 65 years reported by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation in 2017. Although this group of drivers does not fully match our study population in terms of age (ie, some of our patients were older than 64 years, and many were younger than 61 years), the comparative information may be of interest.

It is possible that the Pennsylvania rate is an underestimation, given that less severe accidents (eg, those that did not involve an ambulance or tow truck) might have gone unreported, but our results agree with those of previous studies regarding an increased risk of MVAs in patients with glaucoma. It is notable that the reported rate increased from visit 1 to visit 4 before decreasing at the final visit, which may be attributable to random error (122, or 76%, of the original 161 participants attended the final visit), more defensive driving, or a reduction in driving as the study progressed.

PERIPHERAL VISION AS A FACTOR

Statistical analysis revealed that poorer peripheral vision (mean deviation) in the eye with more severe visual field loss was the most important factor in whether a patient reported an MVA. Less important factors included worse bilateral visual acuity, poorer contrast sensitivity in the eye with more severe visual field loss, and an impaired ability to perform vision-related activities of daily living.

More specifically, in our initial univariate model, increased odds of self-reported MVAs were associated with

- a lower mean deviation in the eye with more severe glaucomatous damage (P < .001);

- poorer bilateral visual acuity (P = .017);

- a lower score on the Spaeth/Richman Contrast Sensitivity test for the more damaged eye (P < .001); and

- a lower total Compressed Assessment of Ability Related to Vision score (P = .073).

In the final multivariate model, only lower mean deviation in the more damaged eye was significantly associated with greater odds of MVAs (odds ratio = 1.09 per 1 dB decrease in mean deviation, 95% confidence interval 1.03–1.14, P < .001).

We should note that a vast majority of the patients in our study would meet or exceed the visual requirements for driving in every state.

LONGITUDINAL DRIVING HABITS

During our study, seven to 10 participants reported each year that they had stopped driving because of their visual acuity and quality of vision. A total of 25% of patients reported driving cessation during the study.

COMPARISONS TO PREVIOUS RESEARCH

In their study of 191 patients with primary open-angle glaucoma, Yuki et al found that 4.9% of patients per year experienced an MVA over the course of 3 years. Visual acuity in the eye with worse BCVA was a risk factor for MVAs.2

Gracitelli et al observed 117 drivers with glaucoma and reported an MVA rate of 9.4%. These investigators did not find an association with standard automated perimetry results but instead with patients’ reaction time and ability to divide their attention.3

In a study of 153 drivers with glaucoma, Tatham et al reported an MVA rate of 11.8% and an association with a low-contrast setting and divided attention during driving simulator tasks.4 In a controlled study, Tanabe et al reported that 3.9% of patients with moderate glaucoma had experienced an MVA, and these investigators found an association with severity of glaucoma.5

Our study population experienced a rate of MVAs ranging from 5.8% to 10.8% per year, most similar to the findings of Yuki et al and Gracitelli et al.

POTENTIAL POLICY INITIATIVES

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide; it can reduce patients’ quality of life and produce functional defects in visual fields, contrast sensitivity, and visual acuity.8-10 The disease is more prevalent in older individuals, and it is estimated that 20% of the US population will be 65 years of age or older by 2030.11 Because almost 80% of older adults in this country live in communities that lack adequate public transportation, they require cars to maintain a comfortable level of independence.12 When these individuals cease driving, they have few options for transportation; they must either rely on family, friends, and caregivers for travel or turn to potentially expensive commercial alternatives. This lifestyle change can therefore negatively affect the quality of life and health of older individuals.

Educating patients who have glaucoma about their risk of MVAs may help to decrease MVA rates. Early identification of patients at risk is also an opportunity to initiate a conversation about driving cessation and other daily tasks that involve concentration, reaction time, and vision. Such discussions may help to bring patients’ expectations into alignment with the physician’s best prognostications and give patients adequate time to prepare for and adjust to a new lifestyle.

CONCLUSION

An aging population presents many challenges. As people live longer and better lives, health care providers must adapt to understand their patients’ evolving needs. Clinicians must also recognize that patients with glaucoma are at increased risk of MVAs, even when their vision deficits are not severe. Educating individuals with glaucoma regarding their safety and fitness to drive can improve their self-awareness and overall well-being.

Practical Tips on Patient Care

By Kara Hanson, OD, FAAO

Conversations with patients about their retiring from driving can be difficult and should not be undertaken lightly. These four practical tips may help your patients make the transition.

No. 1: Make a Referral to a Low Vision Specialist

Low vision (LV) is defined by the AAO as “vision loss which cannot be corrected and interferes with activities, acuity worse than 20/40, scotoma, field loss, or contrast sensitivity loss.” A referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist specializing in LV rehabilitation can be invaluable for addressing not only driver safety but also functional vision as it pertains to daily activities and the psychosocial impact of vision loss. The goal is to improve your patient’s overall independence and quality of life. LV specialists often work closely and coordinate care with other professionals who evaluate a person’s ability to drive safely. According to the AAO, referral to an LV specialist is the standard of care for anyone with LV.

For additional information, watch this video from the AAO: bit.ly/GTPatient. To find an LV specialist near you, visit: bit.ly/GTPatient1.

No. 2: Find a Certified Driver Rehabilitation Specialist

A certified driver rehabilitation specialist (CDRS) will provide clinical and behind-the-wheel assessments to identify your patient’s strengths, weaknesses, and risk level while driving. According to The Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists, “Driver rehabilitation consists of evaluation, training, and vehicle modification recommendations for drivers and passengers with disabilities and age-related impairments as well as counseling and support in the pursuit of maintaining mobility within the community.”1

To find a CDRS near you, visit: bit.ly/GTPatient2.

No. 3: Connect With an Occupational Therapist

Some occupational therapists specialize in LV rehabilitation and may provide clinical driver-readiness evaluations to determine your patient’s level of risk for a motor vehicle accident. As the referring doctor, you will be able to review the results with your patient and decide how to proceed. The testing provides objective feedback for your patient that may help him or her decide to cease driving. If results are borderline, then a behind-the-wheel evaluation with a CDRS is warranted.

No. 4: Provide Options

If you believe that your patient should retire from driving, provide a list of local alternative transportation options. For example, some Medicaid plans cover transportation to doctor’s appointments, and many regional transit companies offer door-to-door rides to people with qualifying disabilities. A social worker should be able to help your patient navigate his or her transportation options. Alternatively, you and your staff can research options online and compile your own list.

1. The Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists. Best Practice Guidelines for the Delivery of Driver Rehabilitation Services. bit.ly/GTPatient3. Accessed October 23, 2019.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Accessed September 1, 2019.

2. Yuki K, Awano-Tanabe S, Ono T, et al. Risk factors for motor vehicle collisions in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma: a multicenter prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166943.

3. Gracitelli CP, Tatham AJ, Boer ER, et al. Predicting risk of motor vehicle collisions in patients with glaucoma: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0138288.

4. Tatham AJ, Boer ER, Gracitelli CP, Rosen PN, Medeiros FA. Relationship between motor vehicle collisions and results of perimetry, useful field of view, and driving simulation in drivers with glaucoma. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015;4(3):5.

5. Tanabe S, Yuki K, Ozeki N, et al. The association between primary open-angle glaucoma and motor vehicle collisions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(7):4177-4181.

6. Richman J, Zangalli C, Lu L, Wizov SS, Spaeth E, Spaeth GL. The Spaeth/Richman contrast sensitivity test (SPARCS): design, reproducibility and ability to identify patients with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(1):16-20.

7. Wei H, Sawchyn AK, Myers JS, et al. A clinical method to assess the effect of visual loss on the ability to perform activities of daily living. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):735-741.

8. Varma R, Lee PP, Goldberg I, Kotak S. An assessment of the health and economic burdens of glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(4):515-522.

9. Hawkins AS, Szlyk JP, Ardickas Z, Alexander KR, Wilensky JT. Comparison of contrast sensitivity, visual acuity, and Humphrey visual field testing in patients with glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(2):134-138.

10. Tuck MW, Crick RP. The age distribution of primary open angle glaucoma. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5(4):173-183.

11. United States Census Bureau. 2017 National Population Projections Tables. www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html. Accessed September 1, 2019.

12. Rosenbloom S. The Mobility Needs of Older Americans: Implications for Transportation Reauthorization. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2003.