Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a type IV hypersensitivity that presents as an acute inflammatory vesiculobullous reaction involving the skin and mucous membranes. A spectrum of disease exists, on which SJS is categorized as involving <10% of the total body surface area (BSA), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) as involving >30% BSA, and SJS-TEN overlap (SJS/TEN) as involving 10% to 30% BSA. The incidence of SJS and TEN range from approximately 1.2 to 6 per million patient-years and 0.4 to 1.2 per million patient-years, respectively.1 Although rare, SJS/TEN can be both devastating and life-threatening, and ophthalmologists play a critical role in managing the acute stage to help lessen chronic sequelae.

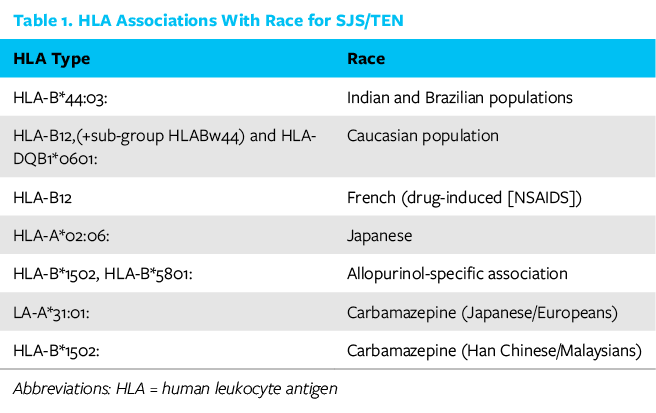

Mortality rates increase dramatically with greater total BSA involvement (eg, TEN). Drugs are the most common etiology, causing approximately 80% of TEN cases and 50% to 80% of SJS cases. The most common drug culprits include sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, NSAIDs, and allopurinol. Various associations between race and human leukocyte antigen type have been described in the literature and are summarized in Table 1. The most common infectious diseases include streptococcal bacteria, herpes simplex, mycoplasma pneumonia, and adenovirus.

A reasonable approach to breaking down SJS/TEN is to separate the disease stages into acute, chronic, and end-stage with the respective ocular surfaces involved (cornea, conjunctiva, and eyelid). This article focuses on acute stage management, an important step to reduce chronic and end-stage sequelae.

ACUTE STAGE

The acute stage represents the initial 2 to 6 weeks after symptom onset or the time until skin and/or mucosal ulcerations resolve. Initial systemic symptoms herald this disease and include fevers, joint pain, respiratory distress, and malaise, quickly followed by the onset of rash, which is classically an erythema multiforme (bull’s eye rash with a red center and pale surrounding ring). If an offending drug is recognized, it should be promptly discontinued. Look specifically for drugs started within the past 8 weeks or increased dosage of a long-standing medication. If no clear offending drug can be identified, all home medications should be discontinued. Mucous membranes that are involved can include the eyes, mouth, and genitalia. Acute ocular involvement occurs in 50% to 80% of SJS/TEN cases and may lead to chronic sequelae in at least one-third of patients.2

Examination. Ocular findings in the acute stage can be highly variable, ranging from minimal conjunctival injection to ocular surface sloughing, and they can include severe inflammation with a bilateral mucopurulent conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and conjunctival/corneal ulceration. Special attention should be paid to the eyelid skin, eyelid margin, conjunctiva, and cornea. Additionally, the palpebral conjunctiva also needs to be evaluated with eversion and fluorescein staining to highlight membranes and epithelial denudation. Sometimes this may be extremely uncomfortable for a patient, requiring coordination of sedation and pain medication administration to facilitate a thorough examination. Evaluation for the degree of conjunctival injection (a marker for degree of inflammation), epithelial sloughing on the eyelid margins/ocular surface, and presence of pseudomembranes and early symblepharon are essential. Saline rinses can be useful for removing mucous and tear film debris that may hide conjunctival defects, which can lead to the development of symblephara when persistent.

CHRONIC STAGE

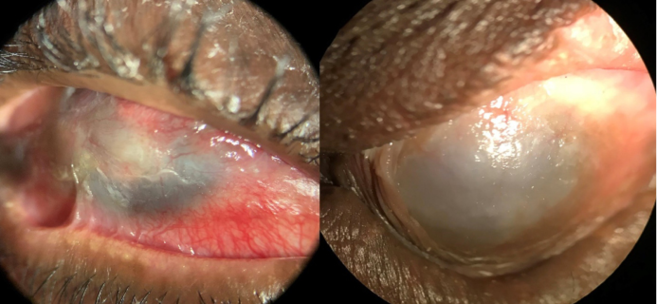

Despite resolution of acute systemic disease and skin involvement, chronic sequelae can develop due to ocular surface inflammation (cicatrizing conjunctivitis) and scarring that damages the eyelid architecture and tear film function. The chronic stage (Figure 1A) is characterized by forniceal foreshortening, cicatricial entropion with trichiasis, and symblepharon. A chronic dry eye is characterized by eyelid margin keratinization with destruction of meibomian gland orifices and conjunctival deficiency leading to subsequent goblet cell loss and lacrimal gland destruction. Advanced symblepharon formation can even lead to a frozen globe. Repeated microtrauma from the keratinized posterior eyelid surface can cause neovascularization, scarring, and limbal stem cell deficiency with subsequent conjunctivalization and persistent epithelial defects. These eyes are at an increased risk of infectious keratitis and corneal transplant failure.

Figure 1 | Chronic SJS with conjunctival inflammation, symblepharon, ocular surface failure, corneal scarring, and neovascularization (A). End-stage SJS with a keratinized surface (B)

END STAGE

The end stage of SJS/TEN is characterized by a dry, keratinized ocular surface (Figure 1B). This end stage results from conjunctival and limbal stem cell loss as a result of repeated trauma and inflammation of the ocular surface.

ACUTE STAGE MANAGEMENT

Identify and discontinue any systemic medications that are potential causes. Management ideally is done in a burn unit with collaboration between intensivist/hospitalist, dermatology, and ophthalmology for management of dehydration and infection. Despite controversy in the efficacy of significantly reducing late ocular complications, systemic therapy such as immunosuppressive medications, intravenous corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin may be utilized. Solumedrol 1mg/Kg daily divided into two doses every 12 hours is a common starting point.

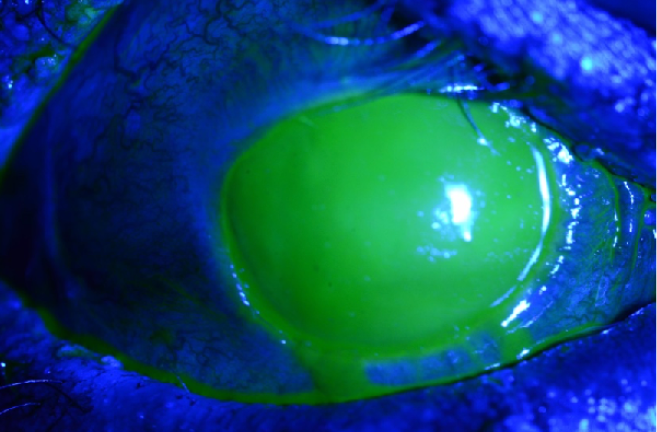

From an ophthalmic standpoint, the main goal from at this stage includes lubrication of the ocular surface, which can be achieved with frequent preservative-free artificial tears or ointment. Lubrication helps improve symptoms and speed reepithelization of the ocular surface. Additional supportive therapy includes saline rinses to remove inflammatory debris, removal of membranes, mechanical lysis of adhesions, bandage contact lens placement, and use of topical antibiotics in the presence of epithelial defects (Figure 2). If exposure is an issue, application of plastic wrap or a Tegaderm (3M) with petroleum jelly can create a moisture chamber; extra care must be taken if there is skin sloughing. Treatment with frequent topical corticosteroids has been shown to yield significant improvement in visual outcomes.3 Other antiinflammatory topical medications such as cyclosporine may play a role.

Figure 2 | Acute phase SJS with a near total corneal epithelial defect

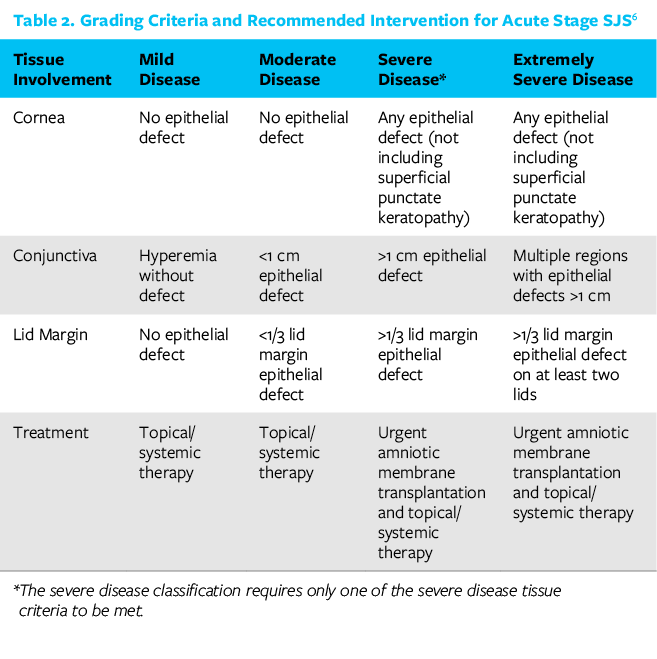

The most significant therapeutic intervention shown to have long-term benefit at this stage is the application of early amniotic membrane covering the entire ocular surface (cornea, bulbar conjunctiva, palpebral conjunctiva) and eyelid margins within the first week of symptom onset or as early in the clinical course as possible (Figures 3 and 4). See Table 2 for indications.

Figure 3 | Sutured amniotic membrane for SJS.

Figure 4 | Ocular surface post sutured amniotic membrane.

Although outpatient amniotic membranes (ie, Prokera, BioTissue) have been utilized at this stage, sutured cryopreserved amniotic membranes are superior at covering the palpebral conjunctiva, peripheral bulbar conjunctiva, and, most importantly, the lid margins (see Step by Step: Sutured Amniotic Membrane Transplantation). Patients in the acute stage are acutely ill, and a trip to the OR with intubation can be life-threatening (depending on disease severity); therefore, we have been performing this procedure under bilateral retrobulbar block with monitored anesthesia care. If necessary, suturing amniotic membranes may need to be performed at bedside under sedation. Assessment of the residual amniotic membrane should be performed frequently, and, if persistent denuded epithelium remains, the amniotic membrane must be reapplied until fully resolved.

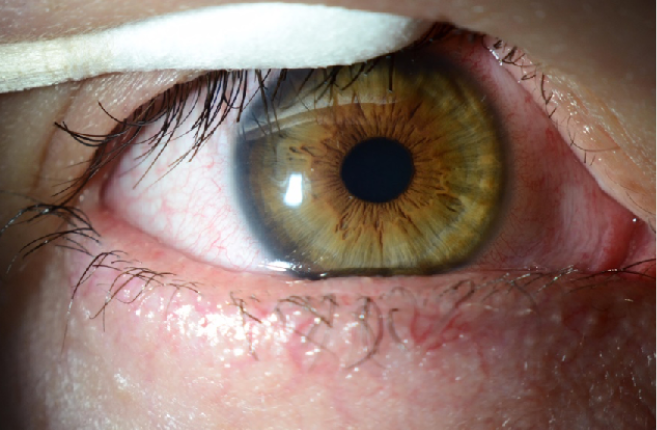

Following the acute course of SJS, patients should be reevaluated as an outpatient within 1 month of hospital discharge, every 2 to 4 months for the first year, and then every 6 months afterward based on clinical course.2 In the chronic stage, management is tailored to severity, but lubrication again remains vital. Other solutions to improve lubrication include punctal occlusion, lid hygiene, autologous serum tears, bandage contact lenses, scleral lenses (eg, PROSE [BostonSight]), and tarsorrhaphy. Systemic steroids (short-term) or immunosuppressants may be necessary in more severe disease in addition to topical steroids if there is uncontrolled ocular surface inflammation. Long-term treatment and visual rehabilitation may require eyelid surgery (eg, mucous membrane graft), keratoplasty, ocular surface stem cell transplantation, keratoprosthesis, and globe-salvaging procedures.4

CONCLUSION

SJS/TEN is a rare systemic disorder with potentially blinding sequelae. Certain critical aspects of care during the acute and chronic stages must be addressed by the ophthalmologist in order to improve the long-term prognosis of these eyes. Preventing irreversible sequelae with appropriate early management can be easier than trying to address them later.

1. Jain R, Sharma N, Basu S, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: the role of an ophthalmologist. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(4):369-399.

2. Kohanim S, Palioura S, Saeed HN, et al. Acute and chronic ophthalmic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis – a comprehensive review and guide to therapy. II. Ophthalmic disease. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(2):168-188.

3. Sotozono C, Ueta M, Koizumi N, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis with ocular complications. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(4):685-690.

4. Dohlman CH, Harissi-Dagher M, et al. Introduction to the use of the Boston keratoprosthesis. Exp Rev Ophthalmol. 2006;1(1):41-48.

5. Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):908-914.

6. Gregory DG. New grading system and treatment guidelines for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(8):1653-1658.