Of all patients’ questions, the ones posed by pregnant women in regard to the safety of their unborn children might be those in most need of an accurate answer. The problem is that, in some instances, the answers are unlikely to be as accurate as we would want them to be. Such is the case with glaucoma in pregnancy and the safety of its treatment for the fetus. The human data are scarce, and the findings of the few reports out there, at times, even contradict each other.

The first time that I wholeheartedly looked into this—beyond reading the single page dedicated to the topic in a textbook—was early in my career, when one of my dear patients with well-controlled congenital glaucoma became pregnant. Pregnancy had not been easy to achieve and, naturally, she wanted all to go smoothly. Needless to say, it encouraged me to dig deeper. What I found were several vague, isolated reports: one small retrospective study in pregnant women, one review paper, and many different opinions and approaches from various glaucoma specialists, all based on the little science we have and their own personal feelings about risk-taking and liability.

For the most part, pregnant women undergoing glaucoma treatment have preexisting glaucoma, such as congenital or juvenile glaucoma, or secondary glaucomas, such as uveitic glaucoma, as opposed to glaucoma newly diagnosed during pregnancy. That gives us the opportunity to have a conversation with our patients before they become pregnant. They should all know that their medical treatment may need to be modified if they plan to become pregnant, that some glaucoma medications could cause harm to the fetus, and that, even though intraocular pressure (IOP) tends to decrease during pregnancy, their glaucoma may or may not progress and will need to be monitored closely. Furthermore, knowing about their plan to conceive ahead of time might give us the opportunity to achieve tighter IOP control if need be by, say, performing that surgery we have been contemplating for a while in a borderline controlled patient, for example.

MEDICATIONS IN PREGNANCY

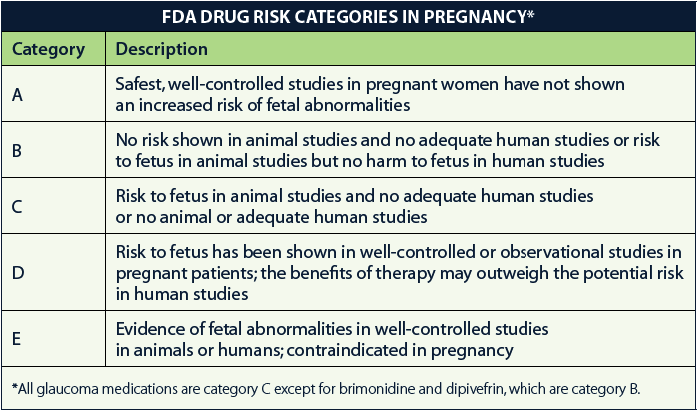

The FDA classifies drugs used during pregnancy by risk categories, as described below.

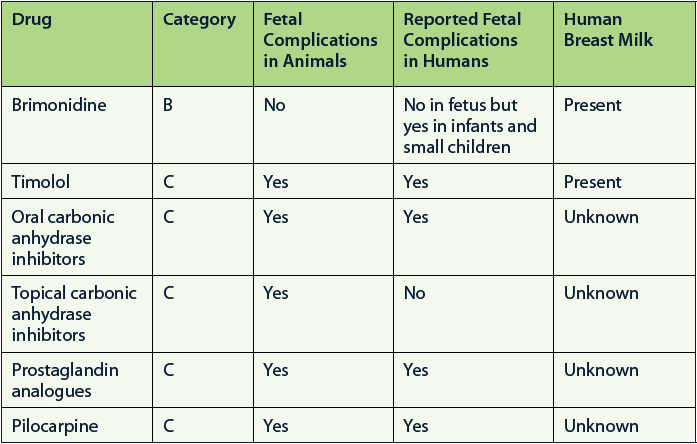

The table below provides a brief visual summary of the current evidence on the safety of glaucoma medications when used during pregnancy.

A bit more information on these drugs follows.

Brimonidine

• Brimonidine is the SAFEST glaucoma drug to use during pregnancy.

• Animal studies in rats and rabbits exposed to doses of brimonidine much higher than those used in humans did NOT reveal fetal damage.

• Brimonidine is excreted in breast milk.

• It is not safe to use in newborns or children younger than 2 years old and should therefore be discontinued near or on delivery and avoided in nursing mothers. Brimonidine can depress the central nervous system and cause apnea, as it crosses the blood-brain barrier.

Timolol and Other Beta-Blockers

• There is one report of arrhythmia and bradycardia in the fetus of a pregnant glaucoma patient using timolol 0.5%. The baby went on to develop postpartum paroxysmal tachycardia with arrhythmia.

• There are several case reports associating topical timolol use during pregnancy with impairment of respiratory control in neonates.

• It is generally recommended for newborns exposed to timolol in utero to be closely observed during the first 24 to 48 hours after birth for bradycardia and other cardiorespiratory symptoms.

• Topical beta-blockers can cause lethargy and confusion in newborns. Betaxolol has a lower risk of causing these central nervous system effects.

• Timolol is actively secreted in breast milk and is concentrated (up to six times the concentration in serum).

• Despite these reports, beta-blockers are commonly used with caution in pregnant women.

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Oral: Acetazolamide and Methazolamide

• Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) can cause forelimb anomalies in rats, mice, and hamsters.

• There are two human reports on their use in pregnant women: one of a sacrococcygeal teratoma and the other of electrolyte abnormalities in an infant born to a mother treated with oral acetazolamide.

• There is also a case series of 12 pregnant women who used acetazolamide 1 g per day for the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension without any maternal or fetal complications, even when medication was given in the first trimester.

• Oral CAIs are excreted in the breast milk of animals, but it is unknown if they are excreted in human breast milk.

• Some physicians always avoid systemic CAIs in pregnant women, while others use them with caution, given the seemingly well-tolerated use for idiopathic intracranial hypertension in pregnant women.

Topical

• There are no reports of any fetal complications with topical use of CAIs in pregnant women or in nursing infants.

• The nursing offspring of rats exposed to high doses of dorzolamide or brinzolamide had decreased weight gain.

• High doses of dorzolamide and brinzolamide have caused fetal complications in animals exposed (from 13 times to 125 times the recommended human ophthalmic dose).

• Topical CAIs are excreted in the breast milk of animals; it is unknown if they are excreted in human breast milk.

Prostaglandin Analogues

• There is a theoretical risk of miscarriage and premature labor with prostaglandin analogues (PGAs). The dosage used to stimulate abortion would be the equivalent of 400 cc of the ocular formulation of latanoprost.

• Of 11 pregnant women exposed to latanoprost during the first trimester, nine had live normal newborns, one miscarried, and one was lost to follow-up. The woman who miscarried had other risks for this outcome.

• Animal studies have found increased fetal death and other complications but at higher doses than those used for glaucoma treatment in humans.

• PGAs are excreted in the breast milk of animals, but it is unknown if they are excreted in the breast milk of humans.

• Most physicians seem to stay away from this drug class during pregnancy. The prescription inserts for the three most common medications of this class state that they can be used when the potential benefits justify the potential risks to the fetus.

• There are no reports of premature labor associated with these medications.

Pilocarpine

• Maternal pilocarpine use has been associated with signs mimicking meningitis in newborns.

• Although safe use of pilocarpine during pregnancy has been reported, its use is not ideal in young patients, given the side effects of induced myopia and brow ache.

SUMMARY

When medically treating pregnant glaucoma patients, it is wise to use the least amount of medications needed to control IOP and to be particularly cautious during the first trimester. It would probably be safest to use brimonidine and topical CAIs. Beta-blockers can also be used with caution. Brimonidine should be stopped before delivery and not used by nursing mothers to avoid any adverse effects on newborns.

The decision to medically treat glaucoma during pregnancy is one to be reached as a team: patient, obstetrician, and ophthalmologist. It is also a good idea to minimize systemic absorption by means of punctal occlusion or by closing the eyes or both. The goal of treatment should be to preserve the mother’s vision while minimizing the risk to the fetus.