The average practice has thousands of lost and overdue patients. A general rule of thumb is that an ophthalmologist who looks back over 5 years of patient visits will find 1,000 to 2,000 patients who have fallen through the cracks. This group comprises a range of patients, from individuals who require only routine eye exams to those with more serious sight-threatening diseases such as glaucoma and cataracts. So, why are there so many patients who have fallen out of contact with the practice? Is it simply a matter of human nature to not be compliant with the doctor’s orders? To answer these questions, it is important to look at real data and dive into the processes that are put in place to keep patients healthy, ensure that the practice is thriving, and help protect the practitioner from legal liability.

Fact #1: Patients Ignore Recalls

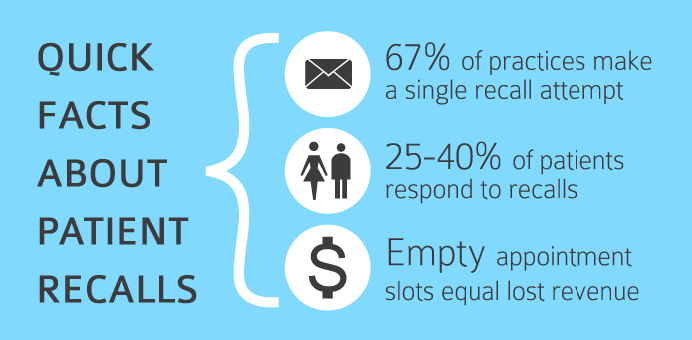

For most practices, the biggest reason patients go missing is because patients ignore their recall notices. It’s difficult for a practice to track recall response rates, and the vast majority of practices don’t have a good handle on it. A study of 16 ophthalmic practices found that the typical conversion rate to a single round of recalls was 25% to 40%.1 This means that, at best, more than half of your patients don’t respond to their recall notice.

Fact #2: Offices Give Up Too Easily

In a separate survey question, 67% of practices said they make a single recall attempt; another 28% indicated they try twice. It is rare to find a practice trying more than two times. Also, most practices rely on a single recall method: mailed postcards. In a follow-up question, the practices were asked if they call patients who don’t respond to recall notices. A full 60% answered “no.” On a side note, many of the practices calling patients admit that they do not do this consistently and that the staff rarely gets through the lists.

Fact #3: Switching Practice Management Systems Results in Lost Data

There are many ways patients can get lost in the data, and all of them can cause havoc with patient retention. One of the most common is switching to a new practice management system. Many practices changed systems as they implemented EHR during the past few years. This is great, except that they often leave the old billing and visit history behind and just bring forward the patient demographics. This creates a problem in keeping patients compliant. If a practice has been on its new system for 6 months and wants to go back and look up patients who haven’t been in for more than a year, it’s very difficult to do so with only 6 months of rich history in the current system. The practice would have to run a query in the old system and then compare it to what is stored in the new system—a task that is tedious and time-consuming at best.

A related scenario is when a practice buys out another practice and is looking to meld the two databases. Keeping one seamless piece of patient history with all of the data elements required to perform accurate queries can be difficult.

Fact #4: Patients Get Lost in the Shuffle

Patients sometimes fall through the cracks and get lost in the data because the patient record doesn’t always have a clear status about what the practice wants to do with them next. These types of problems are usually due to staff error. A common example of this is a patient who walks past the front desk without making a follow-up appointment and the staff does not input the expected return date from which the recall list is generated. Practices are often shocked at how many patients fall into this category where there is no definitive follow-up.

Conclusion

Reactivating your lost patients may be the single easiest way to increase quality of care and grow your practice. Adding even four patients per day should conservatively increase practice revenue by $150,000 annually and add hundreds of patients who need follow-up care. A commitment to the best patient retention process your practice can deliver is fundamental to the long-term health of your patients and business.

1. Gerlach B, Muhlestein T. Recalls, revisited. Administrative Eyecare. 2006;19-23.