The concept of transepithelial PRK is not new, having first been described in 1999.1 Surgeons have always been lured by the elegance and simplicity of removing the epithelium using an excimer laser as opposed to mechanical or chemical debridement. Transepithelial PRK, however, had a low overall adoption rate in the decade following its introduction, and there was greater favoritism of its use for treating complicated LASIK flaps than for mainstream refractive surgery.2-4

The main hurdle to the widespread adoption of transepithelial PRK was that there was no unified, systematic, “plug-and-play” way to perform the procedure. The use of epithelial fluorescence as an endpoint for the initial phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) was subjective at best, and there was a fear of overtreating—and thus losing precious stromal tissue—or undertreating. In addition, it was necessary to modify the actual excimer laser treatment by +0.75 D to offset the fact that the PTK mode would result in a hyperopic shift due to ablation of the central stroma and epithelium removal from the more peripheral cornea. This was neither convenient nor accurate, and the fact that the procedure was split into a PTK and a PRK mode necessitated more planning and resulted in a loss of time spent switching between the two modes, with potential corneal dehydration interfering with treatment accuracy.

Twenty years after the inception of transepithelial PRK, a new approach now holds promise to catapult the procedure into the mainstream of laser refractive surgery all over the world. Single-step transepithelial PRK (trans-PRK) was first implemented on the Schwind Amaris laser (not available in the United States) in 2009. The idea was to use modern improvements in excimer laser integration and engineering to improve an old concept and make it simple, systematic, and consistent. The procedure relies on proprietary software available on the excimer laser platform (in this case, on the Schwind Amaris [ORK CAM software version 4.3.15 and onward]). The laser fires the treatment profile first and then switches seamlessly to a defined-depth radial PTK mode so that the entire laser treatment is performed in one step.

With this approach, there is no need to recenter the treatment or repopulate the patient data. Continuous cyclotorsion control enables precious time to be shaved off the procedure, and stromal dehydration can be avoided. In the radial PTK mode, the laser pulses are applied centrally to peripherally in a parabolic, incremental fashion to mirror the average profile of the epithelial thickness, as published in the literature.5,6 Fifty-five microns of tissue are ablated centrally, and around 65 μm are ablated at the 8-mm zone, obviating the need for +0.75 D of offset correction to the treatment. The software also compensates for the slight differences in photoablation rates of the epithelial and stromal tissue. The diameter of the epithelial removal is calculated to match the total optical zone with the same centration reference, ensuring faster epithelial healing. In addition, the healthy circular or elliptical epithelial edge helps to speed up recovery and visual rehabilitation.

In essence, trans-PRK is a no-touch, all-laser procedure that is performed as follows. First, a speculum is introduced between the eyelids. Next, a polyvinyl alcohol sponge is dipped in balanced salt solution and allowed to expand fully, and then it is applied very gently over the corneal surface in a painting-like motion to avoid unequal wetting of the cornea, which could result in uneven ablation. Pupil registration, together with static and dynamic cyclotorsion control, is initiated, and the laser treatment is applied.

ONE SIZE FITS ALL, WITH CASE-BY-CASE TAILORING

The most common question from surgeons who are unfamiliar with the technique is, “What happens if the epithelium is thicker than the epithelial profile treated by the laser?” There are several case scenarios that may arise. Using the Artemis high-frequency ultrasound, Dan Z. Reinstein, MD, showed that for virgin eyes, central epithelial thickness averaged 53.4 μm (range, 43.5 μm–63.3 μm).5 A study by Karolinne Rocha, MD, PhD, performed using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), corroborated those findings.6 Using those published data, and with the help of computer modeling, we have recreated several potential case scenarios and have determined answers for most of the clinically relevant questions.7

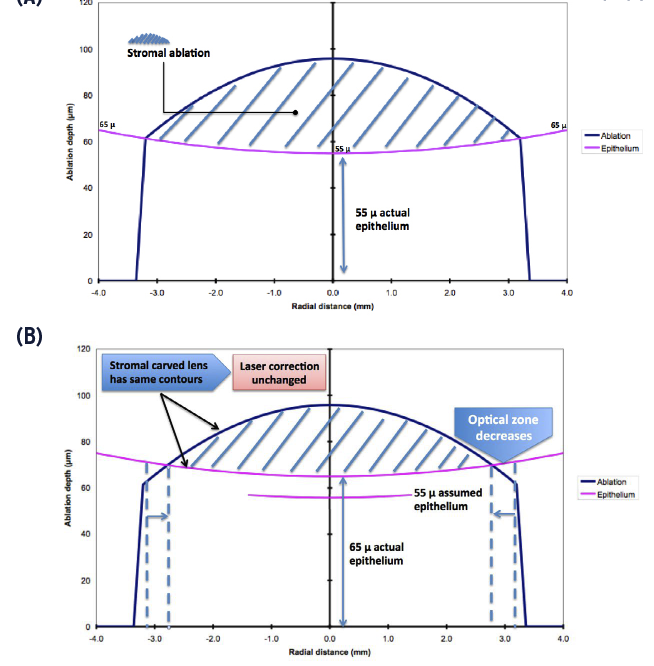

Figure 1. A computer-generated model illustrating the interplay between laser ablation and optical zone in single-step trans-PRK. The epithelium is effectively 55 μm centrally, and the hashed area represents the stromal ablation (A). When the epithelium is 65 μm centrally, the stromal ablation (hashed area) is shown to have the same contours, ie, the lenticular power ablated is still the same, hence the actual laser correction did not change. However, the size of the ablated lenticule has shrunk, and therefore the effective optical zone has decreased (B).

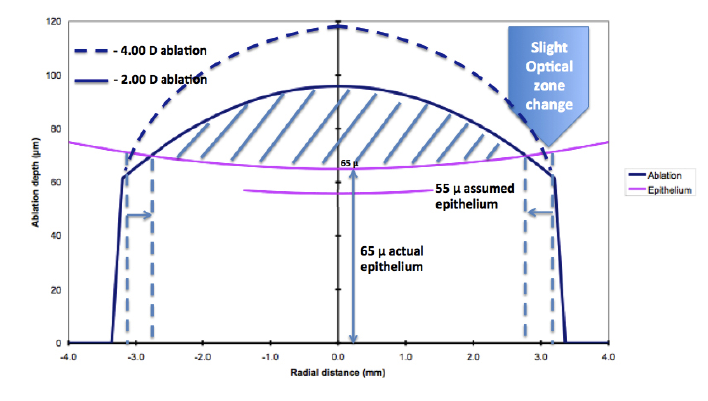

Figure 2. Comparison of a -4.00 D and -2.00 D laser ablation, with a 65 μm central corneal epithelium, more than the laser-programmed 55 μm. As seen in the model, the decrease in the effective optical zone is substantially less the larger the laser ablation (-4.00 D). Clinically, this means that in larger corrections, as opposed to very small corrections, the input optical zone must only be slightly larger than the expected target one. It is interesting to note that the change in curvature of the ablated lenticule (hashed area) is the determining factor in the final laser correction.

If a patient’s epithelium were thinner than the treated profile, stromal tissue will be wasted, and often, it will not exceed 10 μm in a previously unoperated, healthy eye.5If the epithelium were thicker, contrary to what many would think, no undercorrection ensues. Instead, a decrease in the effective optical zone occurs (Figure 1). Therefore, it is important to enlarge the planned optical zone to ensure an adequate effective optical zone. This would seem clinically unacceptable in moderate to high myopes, as such a measure would consume precious stromal tissue. Interestingly, however, the more the myopia to be treated, the lower the decrease in the optical zone, should the patient’s epithelium be thicker than planned (Figure 2). Hence, the planned optical zone would need to be only marginally larger than the expected effective one.

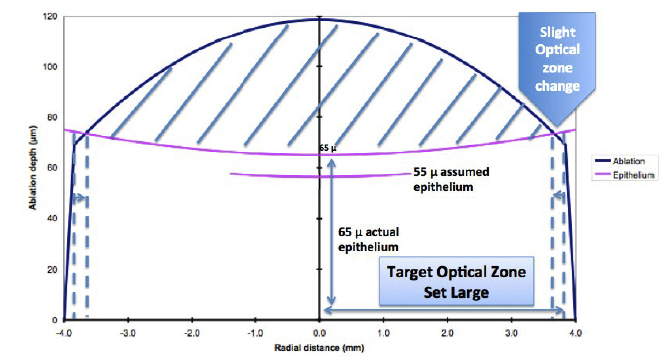

Figure 3. A laser treatment with a substantially large input optical zone, with central corneal epithelium thickness of more than 55 μm, would result in less shrinkage of the target optical zone. The larger the input optical zone, the less the shrinkage in the effective optical zone. This is clinically useful in low corrections.

On the other hand, for patients with low myopia, the optical zone can significantly shrink if the epithelium is thicker than planned; however, based on computer modeling, it seems that the larger the planned optical zone, the less the change in optical zone, should the epithelium be thicker (Figure 3). Particularly in low myopes, significantly enlarging the optical zone (to 7.3 mm, for instance) will not remove appreciable stromal tissue. As for the fact that the epithelium is thicker nasally than temporally and inferiorly than superiorly,5 computer modeling shows that the result would be tilt, which is well tolerated optically.7 Induced astigmatism, however, can ensue if one meridian has a steeper or flatter epithelial profile than the other. Again, taking into account corneal epithelial thickness data in virgin eyes from the literature and using computer modeling, the induced astigmatism should be +0.75 D at worst. Data show that this scenario does not seem to be important in the clinical setting.8,9

CLINICAL RESULTS OF TRANS-PRK

Early clinical results comparing single-step trans-PRK to alcohol-assisted PRK have been encouraging.8,9 Luger et al8evaluated 66 myopic eyes of 33 patients in a prospective, contralateral, comparative study with a 1-year endpoint. Overall, they found that the final results in the trans-PRK and alcohol-assisted PRK groups were similar. The mean UCVA logMAR was -0.07 ±0.09 versus -0.08 ±0.08, the mean manifest spherical equivalence was 0.066 ±0.231 D versus 0.004 ±0.267 D, and the mean astigmatism was 0.164 ±0.288 D versus 0.133 ±0.220 D in the trans-PRK group and the alcohol-assisted PRK, respectively. Fadlallah et al9 conducted a prospective study comparing trans-PRK and alcohol-assisted PRK, with 50 eyes in each group. The investigators observed less pain in the trans-PRK group as well as faster epithelial healing, with 2.5 ±0.6 days for trans-PRK versus 3.7 ±0.8 days for the alcohol-assisted technique. 9

In our experience with trans-PRK at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, we have found that in addition to faster epithelial recovery and thus shorter pain, there is a significantly lower chance of epithelial erosions in the first few days after bandage lens removal and markedly fewer symptoms of subclinical recurrent epithelial erosions in the first 6 months postoperatively. Within 1 week of contact lens removal, very few patients (1%) treated with trans-PRK called the clinic or checked in for symptoms of tearing and sharp pains, which usually denote epithelial erosion, as opposed to 12% in the alcohol-assisted group, many of whom needed an additional bandage contact lens. In a telephone survey conducted in 140 patients (70 per treatment group), 1.4% of trans-PRK patients noted sharp ocular pain and 2.8% experienced “eyelid sticking to the eyeballs,” all in the early morning, as opposed to 15.7% and 10%, respectively, in patients treated with alcohol-assisted PRK.

ADVANTAGES OF TRANS-PRK OVER PRK

There are several inherent advantages of trans-PRK over PRK that make it a desirable procedure to use and to improve, besides the catchy “no-touch, all-laser procedure” marketing slogan. Trans-PRK is patient-friendly, as there is no risk of alcohol spillage and no extra manipulation as in mechanical debridement, reducing patient stress during the procedure. Trans-PRK also provides faster epithelial recovery due to a smaller, healthier, and neater epithelial edge, which translates to a shorter period of patient discomfort. Moreover, as opposed to alcohol and mechanical debridement, laser epithelial removal ensures that no area of Bowman membrane denuded of its epithelium is left untreated by the laser, as the epithelial removal zone is calculated to match the stromal ablation zone. This is an important protective factor against epithelial erosions postoperatively.

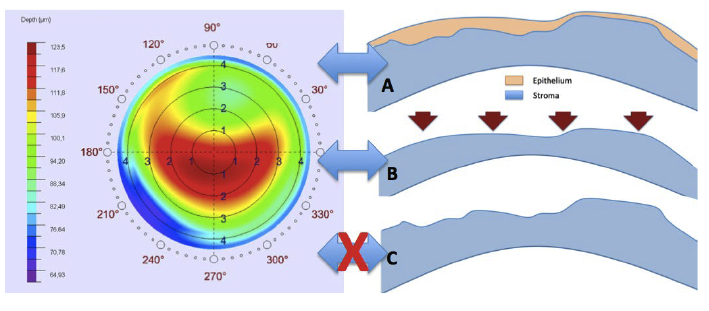

Figure 4. Measured corneal topography and the derived corneal wavefront represent corneal epithelial data (A). In trans-PRK with defined-depth aspheric PTK, the epithelial topography is translated to the stromal surface, which still represents the initial topographic measurement (B). A topography-guided or corneal wavefront-guided treatment would effectively treat the topography measured. In mechanical or alcohol-assisted epithelial removal, the underlying stroma is exposed, and the latter is topographically different (often more irregular) than the epithelium covering it (C). In irregular corneas, conventional, aspheric, noncustomized laser treatments performed with trans-PRK would be more advantageous, as the stroma exposed (B) would be less irregular than with alcohol or mechanical PRK (C).

Another important advantage of a defined epithelial thickness ablation in trans-PRK is in treating irregular corneas (eg, postkeratoplasty eyes, retreatment eyes, and keratoconic eyes in conjunction with crosslinking). In the latter category of eyes, epithelial irregularities are usually much less in magnitude than the underlying stromal irregularities. However, in topography-guided or corneal wavefront-guided treatments, the treatment data are based on the epithelial topography and are lost when the epithelium is peeled, exposing a much more chaotic and unmeasured stromal surface. Trans-PRK ensures that customized stromal ablation indeed treats the topography measured, as the epithelial corneal surface “imprint” is translated to the stromal level by the defined-depth aspheric PTK ablation (Figure 4). Nomogram changes may be required, as, for instance, eyes with previous myopic treatments will have thicker epitheliums in the center, and vice versa for eyes with previous hyperopic treatments, leading to slight undercorrection and overcorrection, respectively, if not accounted for.

In irregular corneas, noncustomized aspheric laser treatment using trans-PRK may lead to a smoother stromal surface for the epithelium to remodel over compared with PRK with alcohol or mechanical epithelial debridement. The latter techniques remove the epithelium, exposing the more irregular stroma, whereas in trans-PRK, the defined-depth aspheric PTK mode will copy the less irregular epithelial topography to the stromal surface, with better chances of the epithelium to remodel again and camouflage the stromal irregularities (Figure 4).

SUMMARY

Single-step trans-PRK is promising, yet the procedure is excitingly still evolving and maturing. Future improvements to the software will allow control over the epithelial profile, in terms of thickness and shape, in order to minimize optical zone shrinkage, save more stromal tissue, and avoid occasional small refractive surprises, especially in complex, irregular, and previously treated corneas. This capability will be even more useful when combined with a fully integrated OCT-driven epithelial data feed, which is becoming a reality with the new generation of OCT systems.

1. Clinch TE, Moshirfar M, Weis JR, Ahn CS, Hutchinson CB, Jeffrey JH. Comparison of mechanical and transepithelial debridement during photorefractive keratectomy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:483-489.

2. Ghadhfan F, Al-Rajhi A, Wagoner MD. Laser in situ keratomileusis versus surface ablation: visual outcomes and complications. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:2041-2048.

3. Buzzonetti L, Petrocelli G, Laborante A, et al. A new transepithelial phototherapeutic keratectomy mode using the NIDEK CXIII excimer laser. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:S122-S124.

4. Kymionis GD, Portaliou DM, Karavitaki AE, et al. LASIK flap buttonhole treated immediately by PRK with mitomycin C. J Refract Surg. 2010;26(3):225-228.

5. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Silverman RH, Coleman DJ. Epithelial thickness in the normal cornea: three-dimensional display with Artemis very high-frequency digital ultrasound. J Refract Surg. 2008;24(6):571-581.

6. Rocha KM, Perez-Straziota CE, Stulting RD, Randleman JB. SD-OCT analysis of regional epithelial thickness profiles in keratoconus, postoperative corneal ectasia, and normal eyes. J Refract Surg. 2013;29(3):173-179.

7. Arba Mosquera S, Awwad ST. Theoretical analyses of the refractive implications of transepithelial PRK ablations. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(7):905-911.

8. Luger MH, Ewering T, Arba-Mosquera S. Consecutive myopia correction with transepithelial versus alcohol-assisted photorefractive keratectomy in contralateral eyes: one-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(8):1414-1423.

9. Fadlallah A, Fahed D, Khalil K. Transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy: clinical results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(10):1852-1857.