Depending on where you work geographically, fungal keratitis may or may not represent a large part of your practice. While training in Miami, I treated fungal keratitis on almost a daily basis, but far fewer cases present to my practice in the Northeast. A confirmed case of fungal keratitis is often met with apprehension, given its potentially devastating course. Fungal keratitis is known to cause corneal perforation and irreversible changes more often than bacterial keratitis.1

As with all challenging clinical scenarios, having a stepwise framework to approach the problem often allays some of the associated fears. Below, I outline the steps that I have found useful when managing cases of fungal keratitis.

STEP 1: CONFIRM THE DIAGNOSIS

On examination, a fungal infection may appear as a suppurative, raised infiltrate with feathery or speculated borders and possible satellite lesions. Although we often suspect fungal keratitis based on clinical examination, confirmation of the diagnosis is essential. Knowing for certain that we are dealing with a fungal infection will avert future frustrations related to medication failure or treatment course. Also, distinguishing between filamentous fungi, such as Fusarium and Aspergillus, and yeast-like fungi, such as Candida, is crucial, as their management differs.

Although corneal scraping is the most common method to confirm suspected fungal keratitis (using stains and cultures), fungi often penetrate into the deep layers of the cornea, resulting in false-negative results. When cultures are negative but my suspicion remains high for fungal keratitis, I perform a corneal biopsy. Under topical anesthesia, I remove a small specimen from the margin of the infiltrate with a 2-mm dermatologic punch, 0.12 forceps, and a crescent blade, taking care to avoid the visual axis and prevent visually significant scarring. This specimen is then sent to the microbiology lab and the pathologist to identify fungal elements. Both cultures and biopsy can potentially delay fungal identification and treatment.

Confocal microscopy is a useful diagnostic tool for visualizing fungi. One limitation, however, is that not all centers have access to this imaging device, and clinicians typically require experience in order to interpret the images.

STEP 2: A MULTIFACETED ATTACK STRATEGY

Topical antifungal agents are the mainstay of treatment for fungal keratitis. Natamycin 5% is considered the most effective medication against Fusarium and Aspergillus. However, it is limited by its inability to cover Candida. Topical amphotericin B 0.15% has activity against Candida and Aspergillus, but it has variable activity against Fusarium. Both medications are poorly absorbed in topical form and therefore are not effective for deep stromal fungal invasion. These deeper infections often require the addition of systemic therapy.2

I approach all fungal keratitis cases with both topical and systemic medications, typically voriconazole or fluconazole. Voriconazole demonstrates excellent activity against filamentous fungi and Candida.3 Furthermore, voriconazole may be administered topically, orally, or via intrastromal or intracameral injection. I sometimes perform intrastromal injections of voriconazole in confirmed fungal cases that continue to progress despite topical and oral therapy. Using a 30-gauge needle, I inject small aliquots into tiny deposits surrounding the infiltrate, just enough to whiten the stroma at each location. Fluconazole is an alternative oral option (also available in topical preparations) that is useful against Candida, but it demonstrates narrow coverage of filamentous organisms. Both medications are typically dosed at 200 mg twice a day. It must be noted that voriconazole is significantly more expensive than fluconazole and may present a financial burden for patients.

Lastly—and this point cannot be overemphasized—topical or oral steroids should be avoided in all suspected and confirmed fungal cases.

STEP 3: BE PATIENT

What often makes the management of fungal keratitis so frustrating is that progress occurs at a painfully slow pace. Patients should be counseled that their treatment course might last several months. Often, there is minimal change on clinical examination from visit to visit, making it hard to determine whether the patient is improving. Many times, I end up relying on the patient’s subjective symptoms rather than the dimensions of the infiltrate on a short-term basis, as often patients feel better before showing signs of clinical improvement.

I initially see patients two to three times per week, until there are definite clinical signs of improvement. I then space out their visits to one to two times per week. With central infiltrates that hinder the view of the posterior segment, it is important to monitor for endophthalmitis using serial B-scans.

STEP 4: CUT IT OUT

If all else fails, cut it out. Surgeons will have different thresholds for when to proceed with surgical intervention. I prefer to treat the fungus medically, as described above, and to delay penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) for as long as possible, given the high rate of recurrence and the poor prognosis of these grafts. PKP may introduce fungus into the anterior chamber or vitreous. Steroids, which are used to prevent graft rejection, may increase the recurrence of fungal infections.

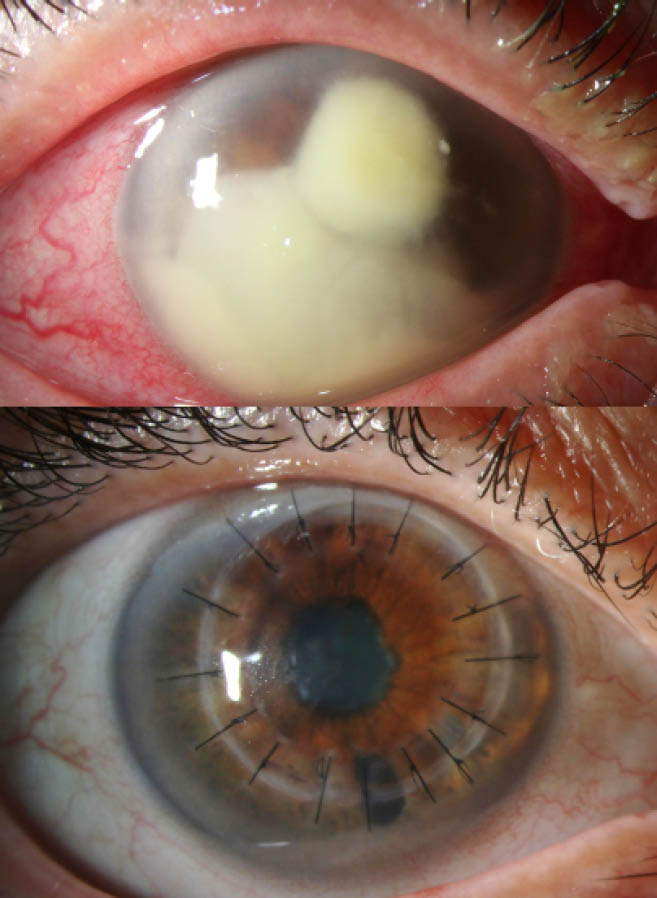

Figure 1 | A patient managed with therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty for Fusarium keratitis. Visual acuity improved from light perception at the preoperative examination (top) to 20/70 at the 2-month postoperative examination (bottom).

However, for cases in which the infiltrate is beginning to approach the limbus, results in perforation, or continues to worsen despite medical treatment, I proceed to PKP (Figure 1). In a study of 52 eyes treated with therapeutic PKP for perforated fungal keratitis, 21% of eyes required a secondary PKP and 85% of grafts remained clear at final follow-up.4 After performing PKP, I typically use cyclosporine at a fortified 0.5% concentration to prevent graft rejection and to avoid corticosteroid use. Cryotherapy or voriconazole injections at the host margins can be combined with PKP for additional therapeutic effect.

Briefly, there is mounting evidence for the use of corneal crosslinking to treat fungal keratitis. A study of Fusarium keratitis unresponsive to standard therapy did show resolution with rose bengal photodynamic therapy.5

SUMMARY

Fungal keratitis is a challenging clinical scenario that may be a source of frustration for both patients and clinicians alike. But the more difficult the challenge, the more rewarding it is to overcome. I do believe that with a methodical approach, we can achieve successful outcomes in the management of fungal keratitis.

1. Wong TY, Ng TP, Fong KS, Tan DT. Risk factors and clinical outcomes between fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparative study. CLAO J. 1997;23(4):275-281.

2. Tanure MA, Cohen EJ, Sudesh S, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR. Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea. 2000;19(3):307-312.

3. Lalitha P, Shapiro BL, Srinivasan M, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Fusarium, Aspergillus, and other filamentous fungi isolated from keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(6):789-793.4. Xie L, Zhai H, Shi W. Penetrating keratoplasty for corneal perforations in fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2007;26(2):158-162.

5. Amescua G, Arboleda A, Nikpoor N, et al. Rose bengal photodynamic antimicrobial therapy: a novel treatment for resistant Fusarium keratitis. Cornea. 2017;36(9):1141-1144.