“Imagine a large river with a high waterfall. At the bottom of this waterfall hundreds of people are working frantically trying to save those who have fallen into the river and have fallen down the waterfall, many of them drowning. As the people along the shore are trying to rescue as many as possible one individual looks up and sees a seemingly never-ending stream of people falling down the waterfall and begins to run upstream. One of other rescuers hollers, ‘Where are you going? There are so many people that need help here.’ To which the man replied, ‘I’m going upstream to find out why so many people are falling into the river.’”

—Saul Alinsky1

In the spring of 1918, a novel influenza virus emerged. Symptoms appeared mild, and the sick recovered rapidly. But, as summer turned into autumn, a second wave hit. Now highly contagious and deadly, the virus—which became known colloquially as the Spanish flu—left a mass of bodies in its wake. Strict quarantine measures were enforced around the world and in areas of the United States. However, officials in Philadelphia did not heed warnings to cancel large public gatherings and allowed the Liberty Loan Parade to take place on September 28, 1918. Within weeks, 13,000 Philadelphians had died from the virus.1 According to the CDC, the pandemic ultimately infected 500 million people worldwide and caused an estimated 50 million deaths.

Throughout history, nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as quarantine and cordon sanitaire, have been used successfully to mitigate the impact of epidemics. Dating back to the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century, the term quarantine is derived from the Italian word quarantenaria, referring to a 40-day period of isolation imposed on travelers upon their arrival from suspected areas of infection.2 Unfortunately, as exemplified by Philadelphia’s response to the 1918 flu pandemic, not all communities are comfortable with temporarily restricting civil liberties, even if it could mean saving lives.

This discord between civil liberty and public health came to the legal forefront in the landmark 1905 Supreme Court case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, after a statute initiated statewide smallpox vaccination. Henning Jacobson, an early opponent of vaccines, refused vaccination and received a $5 fine. Appealing to the Supreme Court, Henning argued that mandatory public health measures infringed upon the Fourteenth Amendment. In support of Massachusetts, Justice John Marshall Harlan declared that individuals did not have “an absolute right in each person to be, in all times and in all circumstances, wholly free from restraint.”3

As it often does, history repeated itself. In December 2019, the news of a novel coronavirus ravaging the Wuhan region of China hit mainstream media. Still, the distance lulled many Westerners into a false sense of security. In recent years, experts have repeatedly warned of the inevitability of another pandemic. In response to the Ebola epidemic, the Global Health Security Index was developed to determine each country’s ability to combat a pandemic in the modern era.4 Although no country was deemed truly equipped to manage such a biologic disaster, the United States ranked first in a number of indicators, including epidemiology workforce, biosecurity, and emergency preparedness. Surely, Americans felt prepared to fight the virus on the off chance it crossed our borders. For the next 2 months, life continued as usual. Then, in what seemed like the blink of an eye, the first community-acquired COVID-19 case arrived in the United States, leaving health care workers and public officials scrambling to catch up.

PREVENTION AND RESPONSE

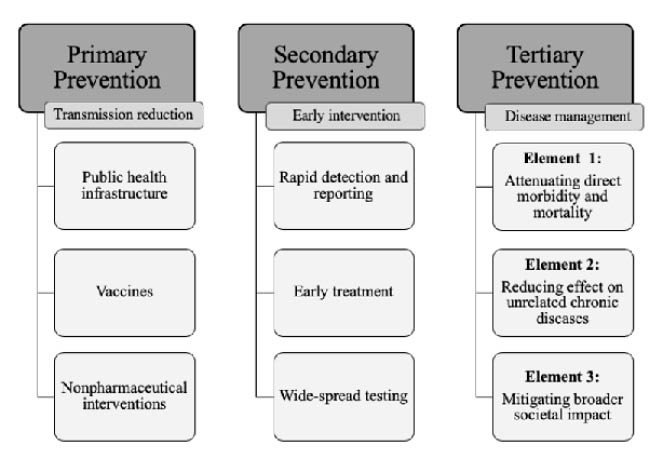

The fight against COVID-19 has called into question societal perspectives on civil liberty and, ultimately, regard for public health initiatives. Pandemics such as HPV-associated cancer and diabetes mellitus fit into the well-known public health paradigm of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (Figure).

Figure | A public health paradigm for pandemic prevention and response.

Primary prevention. Primary prevention, which is composed of a multitiered approach and is essential for effective containment of all diseases, includes health care infrastructure (eg, surge capacity, workforce, sanitation); disease surveillance; and, in the case of infectious diseases, vaccines. Vaccination, however, is limited by the constraints of time-consuming research and development as well as by the supply chain required to match global needs. As we await a vaccine for COVID-19, leaders have shifted primary prevention efforts toward the time-worn tools of quarantine, public education, and behavioral modification.

As resident physicians, we witnessed the decisive actions taken by our institution to enact primary prevention efforts to combat COVID-19. After endless phone calls, difficult triages, and examinations complicated by intense personal protective equipment, all nonurgent ophthalmology visits were postponed. Pathology quickly transformed into a skeleton crew, with staff members working from home or alternating shifts to decrease hospital exposures. Residents in each department were divided into two teams that rotated shifts in order to prevent members of different teams from infecting one another. This decrease in staffing was paralleled by an increase in patients presenting to the emergency room, where our colleagues saw an uptick in intubations and ICU admissions. We watched as coresidents and friends at other hospitals were reassigned to COVID units, and we searched for our retired stethoscopes in the event we too would be called.

Secondary prevention. Despite efforts to slow community spread through quarantine and primary prevention, asymptomatic spread remains a significant challenge today. To this end, secondary prevention in the form of disease detection and early treatment is crucial. At our institution, the pathology department worked tirelessly to rapidly develop an in-house COVID-19 test with a quick turnaround time and, more recently, serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Unfortunately, testing and reporting capacities have lagged across the United States due to regulations that initially prevented the development of such in-house tests.

Tertiary prevention. We have since entered the arduous territory of tertiary prevention—the late treatment and rehabilitation of disease. Tertiary prevention can be divided into three distinct elements. The first and most obvious element, prevention of coronavirus-related morbidity and mortality, has overwhelmed health care facilities around the world. Death rates in the United States continue to climb, and intensive care units have reached capacity. As specialists, we continue to see our sickest patients while most of our resources are reallocated to the emergency rooms and ICUs.

As resources continue to be diverted toward COVID-19, a second element of tertiary prevention is needed: the mitigation of worsening non-coronavirus diseases. Patients with acute exacerbations of chronic conditions have avoided health care facilities due to fear of infection. In our ophthalmology emergency department, a patient presented with a retinal detachment that had initially occurred several days prior. Worried about coming to the hospital for fear of catching the virus, he, in turn, sacrificed the visual potential of his eye. More personally, a friend with systemic lupus erythematosus had to frantically search numerous pharmacies across New York City for her daily prescription of hydroxychloroquine. Pharmacies had run out of stock as increasing rates of over-prescription followed early reports that the medication could improve outcomes of COVID-19.

It is too early to understand the impact of the final element of tertiary prevention: the downstream effects on population health due to COVID-19’s influence on multiple aspects of society. Unemployment rates have surged as virus containment efforts shut down businesses worldwide. The ripples of widespread unemployment and economic uncertainty will have unanticipated consequences globally on population health through mechanisms such as food insecurity, homelessness, and inadequate access to health care. Although this third element of tertiary prevention may hover in our blind spot, it remains crucial in reducing the overall impact of this pandemic.

CONCLUSION

Humanity has confronted the burden of infectious diseases for millennia and will continue to face these obstacles. Optimal prevention requires a unified approach based on a strong foundation in public health paradigms. Although pandemics may be inevitable, our preparation is not. As Saul Alinsky’s famous parable suggests, we must focus future efforts on heading upstream, toward primary prevention. When we emerge from the final stages of this pandemic, will we come together and take actions to prepare ourselves for the future? Can we build a dam on the brink of the waterfall to stop future generations from drowning? Or, do we do what we often do: express gratitude that the crisis is over and hope that history will not repeat itself?

1. Shelden RG, Macallair D. Juvenile Justice in America: Problems and Prospects. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press; 2008.

2. Wirth T. Urban neglect: the environment, public health, and influenza in Philadelphia, 1915-1919. Pa Hist J Mid Atl Stud. 2006;73(3):316-342.

3. Rosen G. A History of Public Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2015: 29-30.

4. Leavitt JW, Numbers RL. Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health. 3rd ed. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1997: 409-415.

5. GHS Index: Global Health Security Index. Building collective action and accountability. October 2019. www.ghsindex.org. Accessed April 12, 2020.