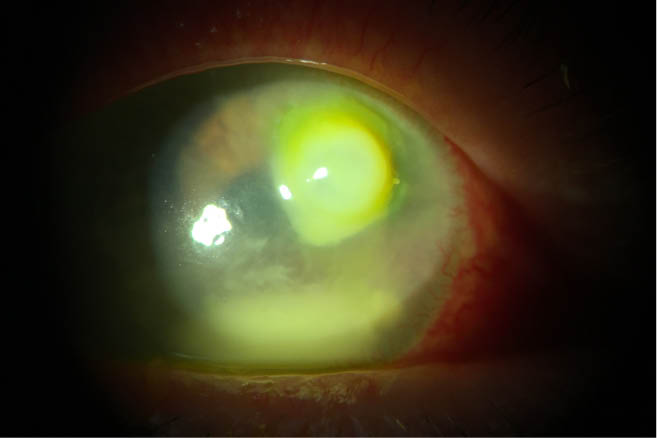

Infectious corneal ulcers are a major cause of visual impairment and corneal blindness worldwide, especially in the developing world, where they are often associated with corneal trauma. In the United States, infectious corneal ulcers are often a result of soft contact lens wear (Figure 1), either as a mode of visual rehabilitation or for cosmetic purposes.

Figure 1 | A bacterial ulcer related to contact lens wear. After the patient was well controlled on an antibiotic drop regimen and healing for 3 to 4 weeks, an amniotic membrane was placed to help minimize scar formation.

Classic corneal ulcer infections that are bacterial, especially among contact lens wearers, often show up first in an optometry office and are then referred to a cornea practice. These infections are particularly challenging to treat because certain types of bacteria can quickly eat through to the cornea and lead to a corneal perforation that might require emergency surgery. If patients do not seek care quickly enough, these infections can rapidly extend and expand, leading to irreversible visual sequelae.

IDENTIFY THE ORGANISM

The conventional standard of care for infectious corneal ulcers is treatment of the infection with targeted antimicrobials, topical steroids, and other measures to heal the cornea. The key to successfully treating a corneal ulcer is identifying the organism responsible for the infection. Infectious corneal ulcers have many potential etiologies: viral, bacterial, protozoan, fungal, or secondary to other rare organisms. Determining the source of the infection may require bacterial, fungal, Acanthamoeba, and viral cultures.

Corneal sensation testing of the unanesthetized cornea revealing significant hypoesthesia points to a possible viral etiology. Clinical observation of injection, ciliary flush, anterior chamber cells, corneal infiltrates, stromal melting, keratic precipitates, or stromal inflammatory cells all indicate the presence of an inflammatory component and therefore require antiinflammatory intervention. Depending on the size and location of the ulcer, I may culture it right on the spot and immediately start the patient on aggressive antibiotic treatment in the form of either fourth-generation fluoroquinolones or compounded higher-dose broad-spectrum antibiotics.

CONTROL THE INFECTION

Once the infection is controlled and the patient is on the appropriate medications, I may introduce an amniotic membrane to help with the final stages of healing. Amniotic membrane tissue is a rich source of biologically active factors that promote healing. This biologically active tissue also supports epithelialization and exhibits antifibrotic, antiinflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antimicrobial features.1 Several amniotic membranes are available for ophthalmic purposes, including the AmbioDisk (Katena), BioDOptix (Integra LifeSciences), and Prokera (BioTissue).

CONCLUSION

The protocol presented above for corneal ulcer treatment provides a clear path to success. Overall, I take an extensive patient history, evaluate risk factors, and culture the tissue. I immediately start the patient on antimicrobials, and, when the culture points to a specific bacteria or fungal infection, I tailor the regimen to target the organism. I follow the patient closely to monitor for thinning of the cornea and possible perforation, and, when appropriate, I initiate placement of amniotic tissue to expedite healing and to help prevent, slow, or minimize scarring.

1. Tseng SC. HC-HA/PTX3 purified from amniotic membrane as novel regenerative matrix: insight into relationship between inflammation and regeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(5):1-8.