I remember it like it was yesterday. On a sunny summer afternoon, a 62-year-old man walked into my clinic with one simple question: “Can you help me see better?” Without having had a chance to examine him or even review his chart, I didn’t know what to expect. I felt eager with anticipation—after all, this is what I had spent most of my life training to do. But, as I quickly discovered, helping this patient see better was going to be one of the most challenging pursuits of my surgical career. In order to proceed, I had to first ask myself, “Am I ready for this?”

THE HISTORY

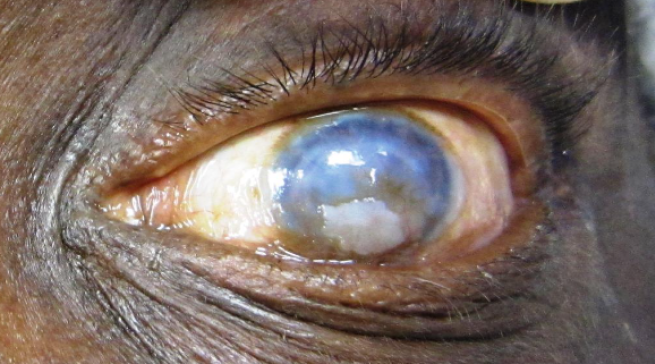

A quick glance at the patient’s chart revealed he had a history of recurrent bilateral herpes simplex virus keratitis. He presented with a 5-year history of hand motion vision at face, secondary to a failed corneal graft (Figure 1). This eye had been through a Gunderson conjunctival flap, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) with cataract extraction and IOL implantation, and then a second PKP procedure. More recently, the patient had also developed secondary glaucoma, which was controlled on topical medications.

Figure 1 | Preoperative photograph of the patient’s failed corneal graft.

Unfortunately, the patient had limited visual acuity (best corrected to 20/80) in his other eye as well, due to corneal scarring from the herpes simplex virus. As a result, he had lost a considerable amount of independence and was feeling increasingly hopeless with each failed transplant. I, in turn, felt compelled to say, “I can do this” and was determined to find a way.

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED

Because continued observation or a fourth corneal transplant were not reasonable options, we decided to do a combined Boston Keratoprosthesis (KPro; Boston Eye and Ear Infirmary) and Ahmed Glaucoma Valve (New World Medical) procedure.

I had a long, detailed discussion with the patient about the various risks of using a keratoprosthesis, including retroprosthetic membrane formation, worsening of glaucoma, endophthalmitis, stromal melt, sterile vitritis, bleeding, and retinal detachment, among other complications. Extensive patient counseling was crucial to the success of this case, given the guarded prognosis for visual improvement. I emphasized that we would need to continue working as a team for the success of this intricate surgery due to the patient’s future indefinite need to wear a Kontour bandage contact lens, inability to accurately check IOP, and lifelong use of ocular antibiotics, steroids, and possibly glaucoma drops. We both developed trust in one another and bonded over this complex case; I needed to know that I could trust him with future compliance, and he wanted to know that I was confident in my ability to help him see better.

Patient counseling and established trust set up a solid foundation for tackling this unique case. The next steps, although time consuming, were equally as rewarding. Due to the cost of the keratoprosthesis and other logistics, I knew the procedure had to be performed in a hospital setting. We coordinated delivery of the KPro device, donor corneal tissue, the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve, and various supplies. Unlike with routine LASIK or cataract surgery, I spent 3 weeks planning and rehearsing the steps of this case, knowing that I may only do a handful of these types of procedures in my lifetime. Although I had previously placed a keratoprosthesis and an Ahmed Glaucoma Valve, I had never done so simultaneously.

I also spent time with the OR team of scrub techs, anesthesiologists, and circulators to ensure that we were all fully prepared for the complexity of this case. I knew instinctively that it would be one of the longest surgeries I would perform, and it was important for the entire team to be on the same page. I carefully researched and reviewed several articles, videos, and past discussions with attending surgeons to prepare mentally, emotionally, and physically.

GO TIME

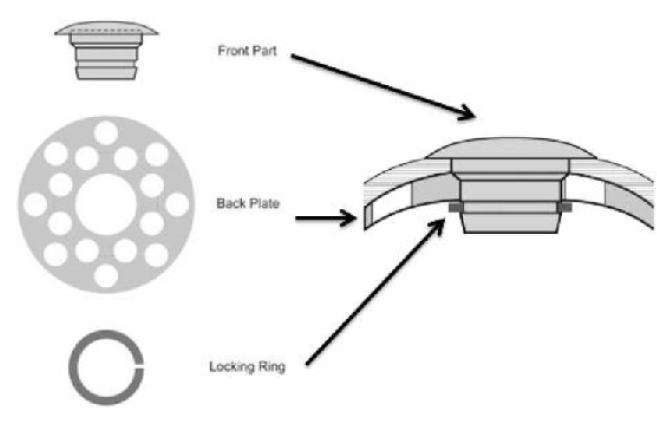

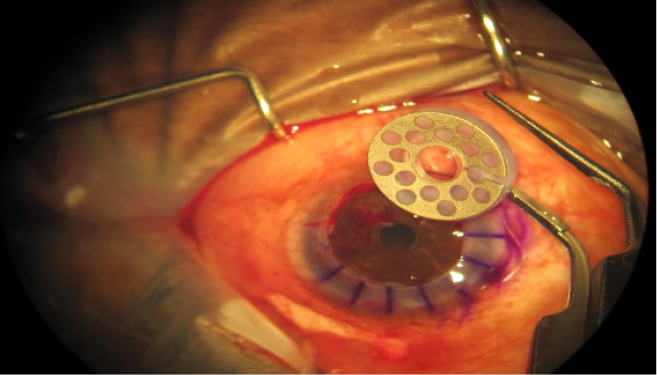

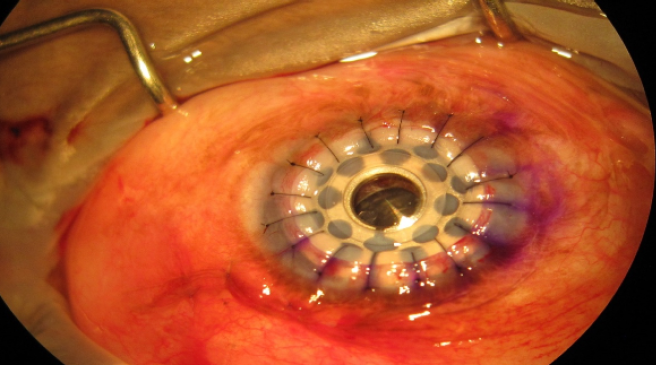

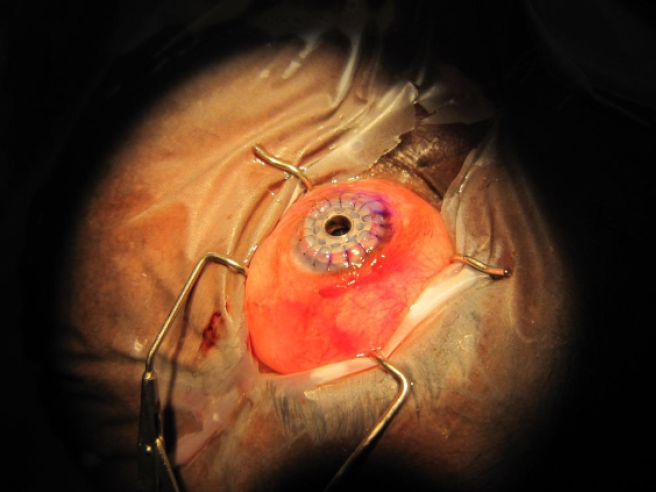

As a result, when it was go time, the case was routine and uneventful. In some ways, it was easier than I expected, given weeks of anticipation, preparation, and discussion. I first secured the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve in the superotemporal quadrant without inserting the tube. Next, I assembled the keratoprosthesis with the front part, donor tissue, titanium back plate, and locking ring (Figures 2 and 3). The failed graft was then removed using a trephine. I was relieved to see a normal pupil and well-positioned IOL after removing the failed, opaque graft. After securing the keratoprosthesis with several interrupted sutures (Figures 4 and 5), I inserted the tube and kept it long enough so that it would barely be visible through the central optical stem. The patient tolerated the procedure very well, and I breathed a sigh of relief, hopeful that this would help him see better.

Figure 2 | Design of the Boston Keratoprosthesis.

Figure 3 | Surgical photograph showing the assembled keratoprosthesis prior to implantation.

Figure 4 | Surgical photograph showing the keratoprosthesis in place.

Figure 5 | Surgical photograph of the keratoprosthesis and Ahmed Glaucoma Valve in place.

The next day, the patient was ecstatic (Figure 6). His vision had already improved to 20/100 from hand motion at face (Figure 7). He has not seen this well in decades and did not even realize it was possible. We approached this surgery in a careful, guarded manner as almost a last-resort option. He was grateful, and I was relieved. Although it can be frustrating to approach a case without knowing what the outcome will be, that is exactly what makes it so unforgettable.

Figure 6 | Postoperative photographs.

Figure 7 | Comparison of preoperative and postoperative photographs.

CONCLUSION

To date, this remains the longest but most rewarding case I have had in more than 10 years of operating, and I gained more confidence and hope from this experience than from any other surgery. The combination of a good team-based approach and careful preparation, research, discussion, patient education, and dedication resulted in a successful outcome. As a result, I now approach other challenging patients and complex cases knowing, “I can do this.”